Sister Marita Rother Remembers Soon-to-Be ‘Blessed’ Father Stanley Rother

She recalls her older brother ‘as a devoted pastor, totally available to his people.’

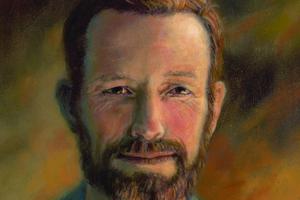

Sister Marita Rother, 81, is the younger sister of martyred Father Stanley Rother (1935-81), the venerable servant of God who will be beatified Sept. 23.

The missionary priest was murdered in 1981 in his rectory amid the violence of the Guatemalan civil war. Sister Marita is a member of the Adorers of the Blood of Christ; she made first vows with the religious community in 1955 and final vows in 1960. The community is headquartered in Rome; its 2,500 members are involved in missionary work, nursing, social work and teaching. Sister Marita has served as a teacher and principal for more than 40 years and currently lives in Wichita, Kansas.

In the 1930s and ’40s, she was one of four children growing up on a family farm in Okarche, Oklahoma. Stanley was the oldest; she was second, 14 months his junior. The close-knit family was committed to their Catholic faith, praying the Rosary daily and participating in the life of their local parish.

Sister Marita, one surviving brother, her extended family and many in her community will join in beatification ceremonies in Oklahoma City. She has been invited to read during the beatification Mass Sept. 23. She recently spoke with the Register about her holy brother, their family and his vocation as a priest.

What are your memories of Stanley as a boy?

He was shy, quiet and very ordinary. He was a down-to-earth, German-Catholic kid. He liked to tease Mom and the kids, although he wouldn’t do that at the Catholic school we attended. In those days, if you got in trouble at school, you got in trouble at home, as well.

He worked the family farm, milking the cows, running the tractor and doing whatever chores our dad thought he could handle. My younger brother still lives on the farm where we grew up.

He displayed leadership qualities. He was a class officer at our parish school, he managed a sports program and served as president of the Future Farmers of America. He was a very responsible person.

You were active in your parish?

Yes, we’d attend events at our church, like the Sunday evening Holy Hours.

Besides Mass, we’d go for feast days. Stanley was a Mass server and knew all the Mass responses in Latin.

What did the family think when he announced he wanted to be a priest?

He was just out of high school, about age 19, when he told us. We supported his decision.

He started seminary in San Antonio, Texas. He struggled academically, though. It was the 1950s, and you needed to master Latin, but he had difficulty with it. He wanted to continue in the seminary, though, so the bishop found a seminary in Emmitsburg, Maryland [Mount St. Mary’s], where he was more successful.

How did he like working as a priest?

From the letters I received at the time, I could tell he was happy with everything except teaching religion at the elementary-school level. He had trouble controlling the kids.

What prompted his decision to become a missionary in Guatemala in 1968?

He had talked to a missionary and took a great interest in it. He learned that they were looking for more priests. So I think I would say he heard the call. He responded to Christ’s invitation, “Come — follow me.”

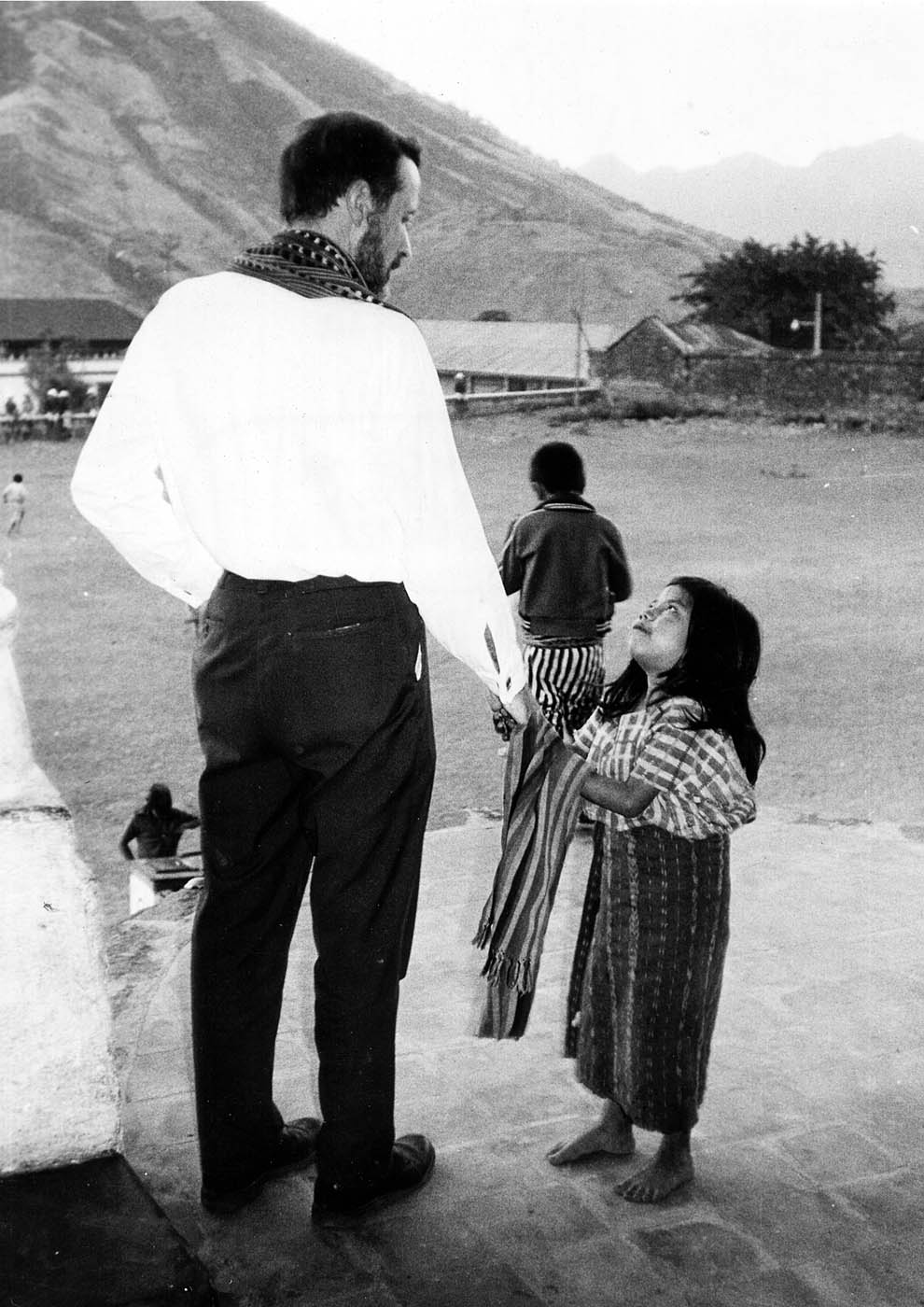

In many photos of Father Rother, he is dressed as a layman and wearing a rainbow-colored stole over a plain white alb. Why is this?

He was at a mission. He’d get his hands dirty working with machinery or in the fields. These were activities that would make it difficult to wear clerical garb. He’d dress differently for the liturgy.

The rainbow stole was a gift from the people he served. Once he learned the language of the local Indians, they claimed him as their priest. They made him the stole, and he wore it.

You visited him twice in Guatemala. What did you see?

Keep in mind that we had lived apart for many years, and we really hadn’t seen each other in action as adults. I consider it one of the highlights of my life, getting to know him better and seeing him work with the people. I was there six weeks the first time, and five the second.

He was a devoted pastor, totally available to his people. He visited their huts, talked with the youth and responded to their needs. I thought it was wonderful what he was doing. He did his work with great energy.

He would help them work their land, encouraging them to upgrade their equipment and try new ways of doing things. You might see him repairing their tractor or pickup truck. He’d go see them in the hospital, take them to the doctor in the city or run errands for them.

Were the people very poor?

Yes. It was poverty I’d never seen before. You’d see children lining the streets, begging for food. They’d try to sell you trinkets. Many of the people were suffering from malnutrition.

He fled the country, but later returned in 1981. What do you know about the political situation there at the time?

I try to avoid commenting on the political situation, but I can tell you he left because he was on the government’s death list. His bishop told him to come home to Oklahoma.

But he was in love with the people. He had done so much for them and wanted to return. He believed in the saying for which he is famous, “The shepherd cannot run from the first sign of danger.”

So he went back in hopes of helping the people be strong in all they had to face. He knew it was dangerous; many of the catechists he had trained had disappeared.

Knowing that his life was at risk in Guatemala, why didn’t he take steps to protect his life or wait until the political situation was more favorable to return?

I don’t think he gave much thought about his safety. He cared about the people; he had given them much strength, and he was their shepherd. He believed he had to return.

What do you remember of the day you learned about his murder?

I was living in Wichita. I was shocked. I didn’t think it would happen. I was very emotional and got very upset. He was my brother. But I and the rest of my family did what we could to cope.

Both my parents were alive at the time. My father was the stronger of the two in coping; I don’t think my mother ever got over it. But I never heard them say, “I wish he’d have stayed home.” I think they believed he was where he was destined to be.

What do you know of his prayer life?

He was very reverent at Mass. Also, once he took me up the mountain to a remote area where he loved to go to be alone. I knew that this was his place of prayer, of spiritual transformation. It reminded me of what St. Peter said on the mountain during the Transfiguration: “Lord, it is good that we are here.”

What are your thoughts on Father Rother’s beatification?

I’m grateful to the Church for recognizing him. I’m proud of him for not giving up, meeting his daily challenges and trusting in God’s promise to give him eternal life. Stanley was one who lived simply, gave his best, and I’m sure has heard the Lord say to him, “Well done, good and faithful servant.”

Jim Graves writes from Newport Beach, California.

- Keywords:

- father stanley rother

- jim graves