Munich Archdiocese Possesses a Wealth of Resources

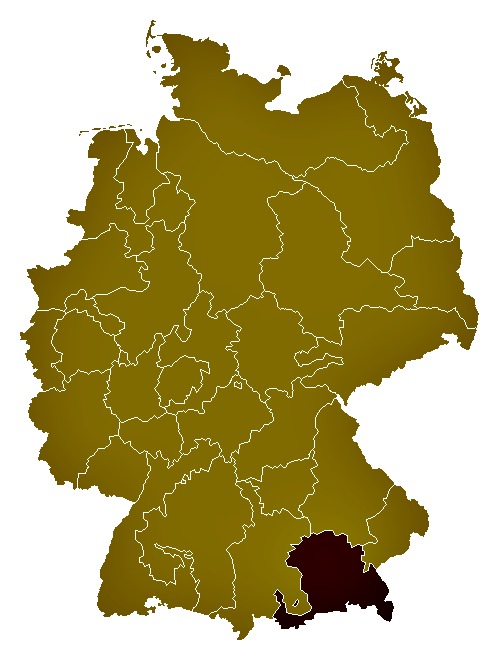

NEWS ANALYSIS: The archdiocesan financial statements reveal it has assets of more than $6 billion, the most of any diocese in Germany.

VATICAN CITY — The Catholic Archdiocese of Munich and Freising has assets of more than 5.52 billion euros (approximately $6.1 billion), making it the wealthiest diocese in Germany, according to German-language press reports, fueling criticism that the Church in Germany has become more of a temporal power than a spiritual one.

Various news agencies, reporting on the archdiocese’s June 20 release of its 2015 annual financial statement, said that the actual figure was higher: The Suddeutsche Zeitung newspaper, under the headline “Blessed are the Rich,” estimated that total assets — including wealth transferred to charitable foundations and “hundreds of contracts and accounts” — amounted to 6.3 billion euros.

The Austrian Catholic news portal Kath.net said it was the highest amount ever recorded by a German diocese, more than the Archdiocese of Cologne, which registered assets of 3.35 billion euros in 2014, and more than the next wealthiest German archdiocese, Paderborn, which has assets of some 4 billion euros.

In its statement, Cardinal Reinhard Marx’s archdiocese gave a lower figure, saying the total assets of the archbishopric amounted to 3.3 billion euros. It noted that the total had fallen by 1.3 billion euros from the previous year, “due to the considerable financial strengthening” of three foundations that led to increased expenditure.

It added that the wealth recorded in the bishopric consists of 1.3 billion euros in tangible assets, “including in particular real estate, such as the new administrative building” in downtown Munich, which opened in April at a cost of 55 million euros. Also included in the figure, it added, were financial assets of around 1.5 billion euros.

“These assets have been invested according to a strict concept of sustainability, the doctrines of Catholic theology and general ecological, social or ethical aspects,” the archdiocese stated, adding that “the working capital” last year consisted of liquid assets of around 440 million euros.

State-Sourced Revenues

The archdiocese said a “strong Bavarian economy” helped strengthen last year’s budget and disclosed that “total revenues” of the archdiocese were 781.6 million euros, of which 570.1 million were derived from the “church tax,” a state imposed levy that accounts for 70% of all revenue for churches (Catholic and Protestant) in Germany.

A further 113.1 million euros were “public subsidies” paid by the state. “Much of this was paid out according to the principle of subsidiarity, by which the state pays institutions that take on some of its duties,” the statement said. Just how much the subsidiarity principle is truly put into practice is debateable, given the likely conditions the state places on the Church in order to offer her such subsidies.

The statement also highlighted that revenues from financial assets, rents, leases and other items “amounted to 166.8 million euros.” It further drew attention to a high level of investment of almost 700 million euros, as well as expenditure on pastoral care, education and personnel costs — the single largest cost amounting to 274.5 million euros (the Church is one of Germany’s largest employers). Supporting the sick, the elderly and refugees, as well as education, social work and other expenses, cost the archdiocese 269.9 million euros.

“Our financial resources are always tied to specific purposes, which serve the faithful and society. Wealth can never be an end in itself,” said Msgr. Peter Beer, the vicar general of the archbishop of Munich and Freising. “Our duty is to manage the resources entrusted to the archbishopric for ecclesiastical duties carefully, conservatively and prudently — and to be accountable for our actions.”

The archdiocese highlighted the fact that, this year, it “recorded and valued its finances and assets in their entirety for the first time” and said that a change from “single-entry to double-entry bookkeeping” had “created transparency.”

This financial openness, which led to the release of a detailed 230-page document on the archdiocese’s finances, was generally well received by the German public. “Even groups that are critical of the official Church praised the transparency with which the Church has disclosed their financial circumstances,” reported Suddeutsche Zeitung.

The archdiocese further pointed out that in the course of this change, large parts of the wealth “have been transferred to foundations supporting the Church’s basic mission.” Once the money is transferred to the foundations, it can only be used for the designated purpose, it said.

These foundations, which carry out ecclesiastical pastoral care and communal life, the Church’s social welfare programs or education, are staffed mostly by experienced commercial and financial experts, thereby guaranteeing independent external control over these financial resources, the archdiocese said.

“The archdiocese no longer has direct access to the wealth of the foundations,” it explained, implying that it no longer has oversight.

The lack of diocesan control over such expenditure has raised questions over whether such a situation is in conformity with Church law. Kurt Martens, canon law professor at The Catholic University of America, believes such “constructions are canonically allowable” as long as the assets have been transferred by the archdiocese to the foundation, “preferably a public juridic person, under the control and supervision of the same archdiocese.”

“Such a transfer, given the sum involved, was most likely subject to a permission [for validity] by the Holy See, in this case the Congregation for the Clergy,” Martens said, adding that this is “not such an uncommon construction.” But he stressed that he was basing such information “upon assumptions” and so, although canonically it seems admissible, closer examination of the canonical statutes and civil bylaws of those foundations, and the transactions that took place, may reveal problems with handing financial control to the foundations.

Spending Priorities

The Register asked Cardinal Marx, who heads the Vatican’s Council for the Economy, which oversees the Secretariat for the Economy, how much of the revenue the archdiocese receives is given to support pro-life groups in particular and how such vast sums of money can be justified when Francis has called for a “poor Church for the poor.”

The cardinal’s press secretary declined to directly answer the questions, sending instead the archdiocese’s press statement in English and a link to all of the financial data.

The vast amounts of wealth in the Church in Germany is thought to have negatively influenced the synod on the family and other papal decisions. Benedict XVI warned about the phenomenon when he visited Germany in 2011 and urged a liberation from entweltlichung (worldliness) to again “become open towards God.”

The Kirchensteuer (church tax) is often cited as a leading cause for the Church’s financial wealth, although some of the amount the Church receives from the German authorities is actually wealth that the Church used to have but which the German state acquired and enriched itself with during the secularization of many churches and convents around 1806, after the end of the Holy Roman Empire.

Still, all German citizens who are officially registered as Catholic, Protestants or Jews pay a religious tax on their annual income tax bill. Revenues for the Catholic Church in 2013 amounted to approximately $6.71 billion, significantly helping to make the German Church one of the wealthiest entities, faith-based or otherwise, in the world.

In a July 17 interview with Schwäbische.de, Archbishop Georg Gänswein dismissed calls to eliminate the tax as well as those who “stylize” it as a great help to the faith, but he said it should not be too high and that it was “a bit much” to throw people out of the Church if they don’t pay it (German bishops have decreed that Catholics who do not pay the tax are not allowed to receive the sacraments, unless in danger of death, although since 2012 it appears non-payment no longer makes one liable to automatic excommunication).

Archbishop Gänswein, who is Pope Emeritus Benedict’s personal secretary, contrasted this with the fact that one can call Church dogma into question and yet receive no sanction.

“The impression gained is that as long as faith is at stake, it’s not so tragic, but as soon as money comes in, then the fun stops.” The “sharp sword” of excommunication for not paying the tax “is inappropriate and in need of correction,” he said.

Asked what the Church in Germany was doing to try to separate herself from dependence on the Kirchensteuer, Matthias Kopp, spokesman for the German bishops’ conference, told the Register that the Church “works with the church tax in a responsible way”; he cited Canon 1263, which gives a diocesan bishop the authority to impose a fair tax for the needs of the diocese.

Kopp said, “There is no doubt in having, and working with, the church tax.”

Edward Pentin is the Register’s Rome correspondent.