One of the advantages of preparing for Triumphs and Tragedies– my podcast series on the Catholic Church– has been the opportunity to get the big picture. You can really understand where you are if you understand where you’ve come from.

The current division and debate within the Catholic Church had not come out of nowhere. Instead, it is the fruit of 500 years of revolution. In getting the big picture of Catholic history one can see that there have been, generally speaking, five hundred year segments.

The first five hundred years is the time of the Early Church and the Roman Empire. The church is hammering out her doctrines, dealing with heresies and coming to a clear understanding of the gospel.

At the end of that epoch the Roman Empire was crumbling and the church enters into a Dark Age. The sixth – tenth centuries were a time of chaos, disintegration of society and corruption, immorality and unbelief in the papacy. If you are unhappy with the reports from Rome and disappointed in the present pontiff cheer yourself up by reading about this period of church history. It was bad. REAL bad.

But during that time period the monastic movement was alive and well. From the West in Ireland and from the East in Italy and from the South in Egypt monasticism was growing. Small Christian outposts were established which were havens of light, love, hospitality, security and strength. They established the foundation for the next epoch.

From 1000-1500 we have the Middle Ages–otherwise called Christendom. The seeds planted by the monastic movement flourished into the greatest age of learning, art, architecture, music and civilization the world has ever seen.

All of this was broken in the sixteenth century which ushered in what I call the Age of Revolution. The Protestant Revolution, the Wars of Religion, the English Revolution, the French Revolution, the Russian Revolution, the Italian, the Spanish, the American, the Mexican….not forgetting the industrial revolution, the technological revolution and not least, the sexual revolution.

In the midst of all this, in these last 500 years we have seen one attempt at revolution after another within the Catholic Church. The Protestant revolution was the first, but then the revolution of the so-called Enlightenment, the French revolution, the revolution of Biblical criticism, then revolution in the 19th century in the form of liberalism, and then in the 20th century the revolution of modernism.

In each of these challenges the revolutionaries meant well. They were idealistic. They wanted a better world. They wanted many good things and they also wanted the Catholic church to “get up to date get with it and get on board.”

This presents the very real question therefore: How much of the Catholic faith is determined by the culture and circumstances in which it was formed and therefore how much of it should change when the culture and circumstances change?

Those who say, “The Catholic faith never changes. It can never change!” are naive. The “faith once delivered to the saints” may not change, but the expression of it and the proclamation of it and the way it is lived out is flexible. It changes whether we like it or not.

The challenge of modernism is this very question. Faced with a rapidly changing world (and the pace of change has only snowballed further) the modernists of the early twentieth century (like the liberals before them) insisted that the church must change and accept the new understandings brought about by science and increased learning. They said it was perfectly possible to change and that the models of thought and expression that worked well enough in the Middle Ages had to be abandoned, or if not abandoned, they needed to be adapted and modified to suit the modern age.

To understand the present troubles in the church, therefore, it is worth taking a few moments to go back and listen to the leaders of the modernist movement. When you understand what they were saying and why they were saying it you will understand better what is going on in the church today, because modernism is a Hydra monster. Pius X may have cut off one head. Many more have sprouted.

Alfred Loisy (1857 – 1940) was a French theologian and Bible scholar. Contrary to the tradition, he taught that the first five books of the Bible were not written by Moses, but they were the result of development, editing and later compilation and redaction. In fact all the historical texts of the Bible were composed in a similar manner. In 1903 he published The Gospel and the Church which was the first step of a complete re-interpretation of the Catholic faith for the modern world.

According to Loisy, historical research and rational thought demanded that the Nicene understanding of Jesus Christ as “God from God, Light from Light, consubstantial with the Father” had to be abandoned. Jesus, he argued, was a Jewish prophet who announced the imminent end of the world and died a political martyr who had no intention of setting up a church or establishing sacraments. The church developed out of historical circumstances in the Roman empire and the dogmas that were defined were merely the summary of the church’s understanding and experience at the time. Having been determined by their particular time period, they should be adapted accordingly to other times and cultures.

This goes along with his concept of “vitality”–that the necessities of life dictated the true forms of religion. Complementing this on the morality side of things was his emphasis on the individual conscience. Conscience was the way the individual discerned what was valuable and true from the historic religion the Catholic had inherited. Loisy said the church did not intend to preach fixed, unchanging dogmas, but simply a message of hope embodied in the idea of the Kingdom of God–a community of caring, sharing, peace and justice.

A contemporary of Loisy was Maurice Blondel (d. 1949) who taught that religion should start not from the objective supernatural revelation, but from the needs of man and evangelization began with the longing and desire of man who, once he was enlightened would come to understand that he needed God. Meanwhile Lucien Laberthonniere (d. 1937) suggested that dogmas were not mysterious formulas of truth, but were only useful inasmuch as they helped inform moral decisions.

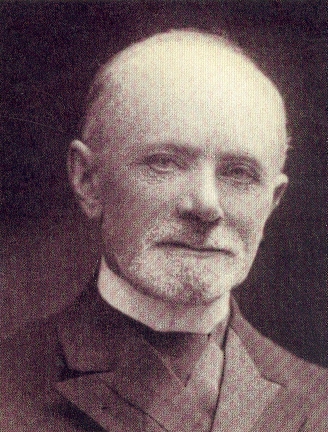

On the English side of the channel George Tyrell SJ thought the scholastic approach to theology (the heavily philosophical method based on Thomas Aquinas) made Catholicism dry, dogmatic, legalistic and hidebound. He called for an experience of the individual grounded in “the absolute imperatives of the conscience.” Like Loisy, he thought the dogmas were simply the attempt at a particular time and within particular historical circumstances to formulate what could be said about this elusive thing called “Truth”. The hierarchy of the church could only ever be the spokesmen of the people and “infallible” statements were a way of saying “the church is trying hard to make sense out of something beyond our imagining”.

OK. So Pope St Pius X stomped on modernism, but the crackdown was only temporarily effective. The same themes bounced back in the Second Vatican Council, and they are still with us today.

Consider what drives elements of the present papacy and those who are using it to change the church. The relativism of the modernists is all around us. Do you see the emphasis not on dogma and defined moral teaching, but on “mercy” and “being flexible”? Do you see the emphasis on the church as an agency of peace and justice rather than the means of salvation? Do you see the downgrading of the sacraments and the de-emphasis on Jesus Christ as the divine Son of God and the emphasis instead on Jesus as a nice guy, a kind person, a martyr, a teacher, a preacher and anything BUT the Son of God? Do you see the emphasis on moral relativism? Why? Because according to the modernists the moral teachings and the dogma are determined by the circumstances and culture in which we find ourselves.

It is easy to condemn all modernism and attempt to squelch it, but that approach doesn’t work. Instead the darkness is best banished by the light. What the church needs now, as we are still reeling from the weakening effects of modernism, is a new orthodoxy that expresses the ancient faith and proclaims the doctrines and moral teachings of the faith in a way that is vital, dynamic and alive in the 21st century.

We will do this with words, but most of all we should do it with works. When we live this faith it is attractive, alive and real.

It’s important to note that Loisy, Laberthonniere and Tyrell were all priests. Down through the ages, heresies were instituted to a large extent by the clergy. The Church used to do a very good job of addressing those threats quickly and fiercely. She benefited not only in defeating the heresies but also in establishing dogmas that have stood the test of time and enlightened the faithful. Not so much these days. Alas.

[…] News Even Now Thousands of Americans Converting to Catholicism Every Year – Boston Globe The Roots of Modernism – Fr. Dwight Longenecker The Rise of the Gnostic Liberal State After Christianity – […]