Although soldiers have been wearing head protection since at least the 26th century BCE, the modern military helmet is a fully 20th century invention.

And it's been a rapid evolution. Growing from its WWI origins, the standard issue Army helmet has transformed from a simple ‘tin hat’ into an impenetrable shell that can shrug off high-velocity bullets. What was once a simple piece of steel is now fabricated from space-age composites that can stop a AK47 round dead in its tracks.

Now, more than a century after the first U.S. Army helmet was introduced, the Army’s Program Executive Office for Soldier Protection and Individual Equipment is reimagining the helmet into a piece of gear more fitting today's battlefield.

This is the 100-year journey of the U.S. Army helmet.

Helmets Make a Comeback

With the widespread introduction of gunpowder in the 16th century, European infantry started ditching their armor. Pikes and swords were less of a threat than musket fire. Even heavy armor was of limited use against bullets, and soldiers had too much to carry anyway. Although a few cavalry units held on to helmets and breastplates, the infantry lost them long before the start of the First World War, and soft hats or caps were standard issue.

During WW1 though, one type of weapon proved particularly lethal: fragmentation shells exploding above trenches. In 1915, armies hurriedly introduced helmets, widely known as ‘tin hats.’ The soldiers found the new helmets comical.

“We shrieked with laughter when we tried them on, as if they were carnival hats,” according to one French soldier, but they cut head injuries from 70 percent to 22 percent.

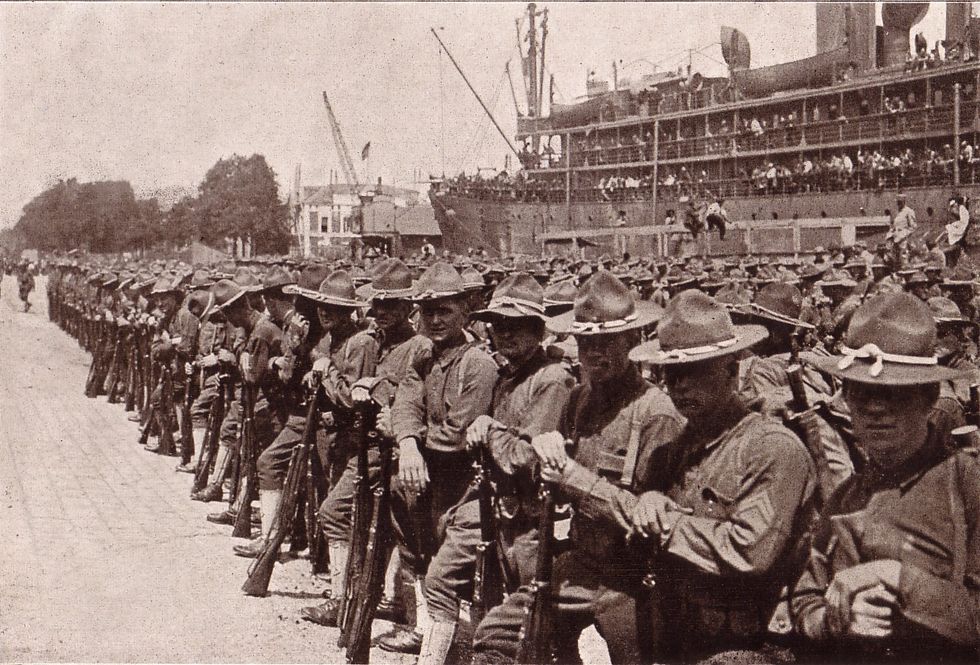

American troops were issued with the M1917 Kelly helmet, copied from the Brodie helmet developed by the British. The design was basic, just a sheet of manganese steel pressed into a bowl shape, weighing about a pound and a half. It came with a basic liner to stop it from rubbing, and a leather chinstrap. This strap could be a liability: once tightened it was difficult to undo, a deadly consequence for a soldier who gets accidentally snagged on some obstacle.

The Kelly was also uncomfortable, but it gave life-saving protection from shell fragments. It was normally painted olive with an anti-reflective coating, but different units soon introduced their own color schemes.

The Kelly helmet was advertised as being able to stop a .45 caliber pistol bullet at 600 feet per second, but this may have given a false sense of security. In the real world, even low-power .45 ammo reaches 800 fps or more, and the 9mm pistols used by the Germans had far greater penetration—as did all the rifle and machine-gun bullets tearing across No Man's Land.

A World War II Icon

Only minor changes were made until 1942 when the Army rolled out the iconic M1 helmet, famous from a thousand war movies from Sands of Iwo Jima to Saving Private Ryan. This is likely the helmet you picture when you imagine a G.I. in full uniform.

The distinctive design has a brim at the front to keep rain off the wearer’s face, and while the M1 was not much thicker than the Kelly, it covered more of the side and back of the head than its predecessor.

The M1 might not be able to stop a bullet, but it could slow one down. In February 1945, during an action against the Japanese in the Philippines, Sgt. Amelio Pucci was shot and went down with a hole in the center of his helmet. His squad assumed he was dead, but Pucci got up minutes later, with a minor head injury but very much alive. Almost all the bullet’s force had been spent in penetrating the M1.

Notably heavy at almost three pounds, the M1 was made more comfortable by adjustable webbing, which could be tightened or loosened to give a better fit for individual skull sizes and shapes. It also had a canvas strap with a quick release to prevent being caught. The liner could be easily removed so the metal shell could be used as a bucket or washbasin in the field if needed.

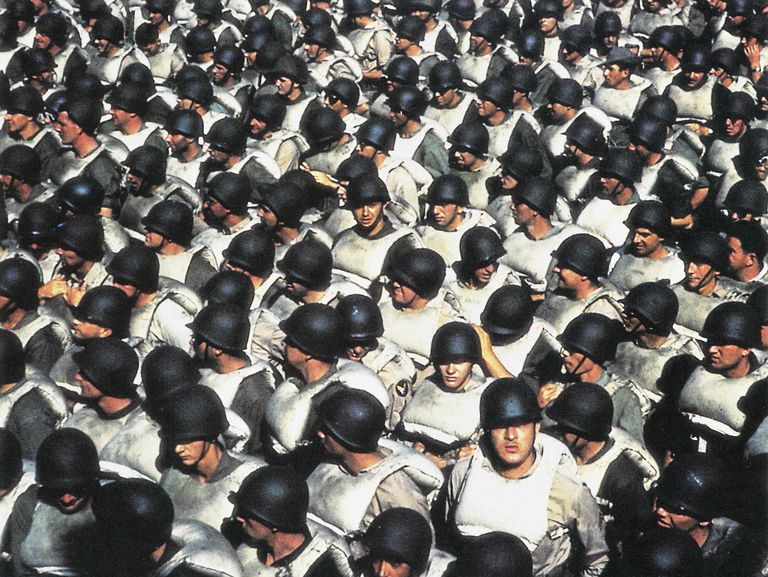

Over 22 million M1 helmets were produced by the end of WWII, and the ‘steel pot’ was so effective that it continued protecting noggins during the Korean and Vietnam wars. The adjustable one-size-fits-all design meant that it could be easily mass produced yet still be suitable for every G.I. It hit the sweet spot of providing adequate protection while being (just) light enough.

The M1 has been described as the most successful helmet of all time, given its service history spanning forty years. The design was copied by many other countries. If it had a competitor for this title, it was the distinctive WWII German Stahlhelm helmet. The Stahlhelm provided similar cover to the M1, but was more complex to manufacture, being made of several sheets of steel, and it was produced in different sizes. The Stahlhelm gave a clearer field of view, something that U.S. designers picked up for their next iteration, and it boasted a sinister accolade—it was the model for Darth Vader’s helmet.

Bulletproof Kevlar

But as wars changed—and space-age materials became more readily available—the Army evolved to face new challenges.

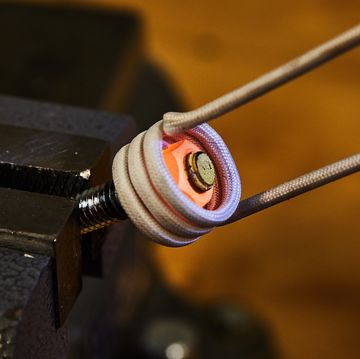

First introduced by Israel army helmets, Kevlar, a newly discovered bulletproof material, also made its way into the U.S. army helmet. What makes Kevlar fabric so effective is that it's impregnated with resin to produce a shell, which is lighter and tougher than steel. Along with Kevlar body armor, the helmet formed the Personnel Armor System for Ground Troops of PASGT, pronounced ‘pass-GET,’ introduced in 1983.

The PASGT helmet was popularly known as the “K-Pot” (for its Kevlar composition) or “Fritz,” for its resemblance to the German Stahlhlem. It provided greater coverage, down to the nape of the neck and had far better ballistic performance. It also featured a removable sweatband.

Kevlar gave a marked improvement in protection. Not only could it stop .45 caliber rounds moving at realistic speeds, the PASGT could also stop the more common 9mm and even bullets from Magnum handguns. During Operation Desert Storm in 1991, the combination of Kevlar body armor and helmet kept G.I.'s incredibly well-protected.

Not quite bulletproof—but close.

21st Century Upgrades

The K-Pot was succeeded by the Advanced Combat Helmet or ACH in 2002. This is made from a combination of Kevlar and a modern ballistic fiber called Twaron. Other improvements included a shock-absorbing liner to provide better protection against violent impacts, like when a vehicle is struck by an IED.

Part of the aim of the new design was to improve the field of vision and hearing. Unlike previous helmets, the ACH was designed to be worn in conjunction with other items of modern military equipment. The front opening can accommodate sunglasses or goggles for eye protection in desert conditions. A clip at the front allows devices like night-vision goggles and cameras to be attached, and the shape has been modified to be compatible with communications headsets.

The ACH was also compatible with nuclear, biological, and chemical (NBC) equipment. Rather than being a standalone item like previous helmets, the ACH had become part of an integrated ensemble.

While the ACH is only supposed to be proof against handgun bullets, it proved surprisingly tough. Tom Alberts was on patrol in Afghanistan in 2012 when something hit his helmet and knocked him down.

“I think I got shot,” he told fellow guardsman Adam Riediger.

Alberts was right: Army analysts later determined his ACH had been struck by an AK-47 bullet, which the helmet stopped completely.

Then in 2011, the Enhanced Combat Helmet arrived. Externally, it closely resembles the ACH.

“You'd have a tough time telling the difference,” project manager Col. William Cole told a media briefing.

The ECH is somewhat thicker, though lighter, but there is a huge difference in the protection it provides. Rather than Kevlar, the ECH is made of ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene, or UHMWPE. This is a special form of the same plastic used to make drink bottles, sandwich wrap, and plastic grocery bags. However, the helmet itself is made from much larger molecules with chains of atoms a hundred times longer than regular plastic.

And the ECH doesn't just stop pistol rounds, as demonstrated during an insider ambush at Camp Maiwand in eastern Afghanistan in 2018. During the ambush, Staff Sergeant Steven McQueen was hit in the head by a truck-mounted machine-gun bullet from twenty feet away. This is a considerably more powerful round than the AK-47 that hit Alberts. McQueen was knocked flat, but was up seconds later, the bullet was stopped by his Enhanced Combat Helmet.

The ECH also provides outstanding protection against shell fragments. Just how good is not exactly known: the Army lab was unable to fire fragments fast enough to penetrate it, so they could not determine the “V50” figure for the velocity at which 50 percent of the projectile penetrates. But one thing was certain—the ECH was superior to anything in the army helmet's 4,500-year history.

A More Modern Helmet

But now, even this ECH helmet, engineered with science for maximum protection, is now being replaced with the Integrated Head Protection System, or IHPS.

“We have already equipped the Security Force Assistance Brigade 2 (SFAB2) with the Integrated Head Protection System,” Lt. Col. Ginger Whitehead, the U.S. Army’s Product Manager for Soldier Protective Equipment, told Popular Mechanics.

The IHPS benefits from what the Army call a ‘boltless retention system,’ which means that it does not need to have holes drilled in the shell to accommodate the chinstrap arrangement. These holes weaken the shell, so the boltless arrangement makes the IHPS substantially stronger. It also provides more coverage.

“We've seen horrific facial injuries on turret gunners from IEDs, thrown rocks, and road debris,” says Whitehead. “To mitigate some of these injuries, we developed an attachable visor and mandible protector that snaps onto the Integrated Head Protection System.”

The optional maxillo-facial protection module makes the helmet look a little like something out of Halo, covering the lower face while also adding a visor. In addition, the IHPS has padding which gives 100 percent improved protection from blunt trauma compared to the ECH.

Instead of the assembly of different brackets that had built up on previous helmets, the IHPS has two universal attachment points able to accommodate any device, such as night vision systems. The IHPS is also available in a wide range of sizes, and the retention system has been redesigned so the wearer can adjust it to their personal preference.

This reflects an increased effort to produce a helmet that is as comfortable as possible. Helmets are only effective if they are worn, so making it as easy to wear as possible increases the helmet’s chance of saving a life.

The next-gen version of the IHPS will provide even better protection when it is issued in 2020. Meanwhile the researchers at the Army’s Soldier Protective Equipment team are looking for further improvements as they gather feedback on users’ requirements and how the equipment performs in the field.

The next quantum jump in protection may come with graphene, an ultra-strong carbon-based wonder material, or even with materials based on spider silk (already being tested in body armor). Such materials have the potential to make helmets lighter and stronger than ever, but right now neither can yet be produced in the quantities required to outfit the world's largest fighting force.

Another likely development is the extension of maxillo-facial protection into full-face ballistic helmets. The U.S. Army is working on an 'individual visual augmentation system' with an augmented-reality display showing targeting information and other data overlaid on a screen, showing data from drones or other remote sensors. This Iron Man-style helmet could also be integrated with a full suite of electronics, as imagined by Special Operations Command’s TALOS armored exoskeleton.

Things have changed a lot since the mud-filled trenches of WW1. While modern warfare now involves stealth fighters, high-energy lasers, unmanned drones, and hypersonic missiles, the soldier on the ground still plays a vital role. And as long as that truth remains, the U.S. Army will keep producing newer and better combat helmets.

“We owe it to the soldiers,” says Whitehead.