“I was a hobo,” Willy Howard told me. “So was my wife.”

It was almost 30 years ago, and I was flat on my back in a hospital bed in Trenton, New Jersey, sharing my room with this elderly man. I called him Mr. Howard. To everybody else, he was Willy. I was in my early 30s, laid low by a bacterial infection and feeling like I’d been hit by a truck. My roommate was in his 90s, and though he was in for heart trouble, he was sharp as a razor.

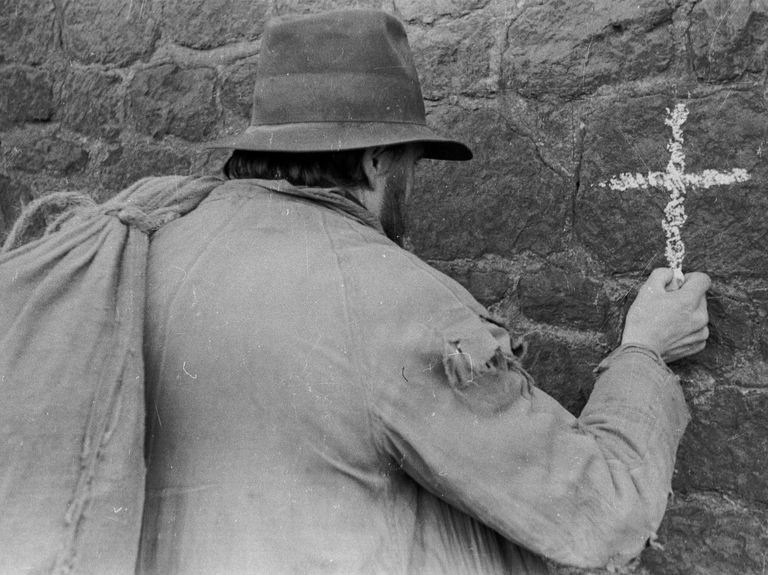

While we healed, Willy imparted wisdom about the difficult truths of life as a hobo, an itinerant worker who moved through rural America, sometimes stealthily for their own security. Their secret? A system of hastily scrawled symbols that only the initiated would understand.

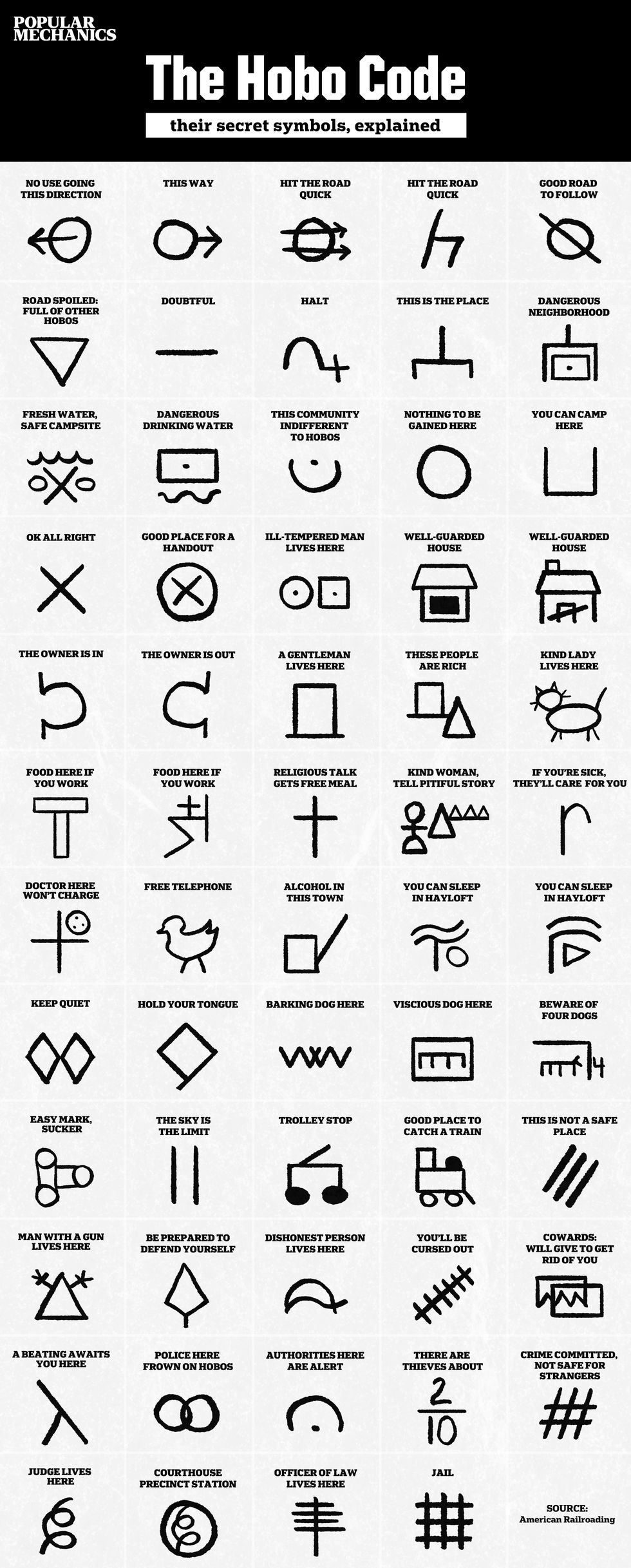

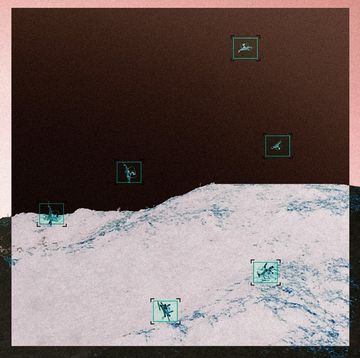

These symbols, really hieroglyphs, appeared on posts and bridge abutments, on fences and outbuildings. Hobos scrawled the secret language with whatever writing implements were available—a lump of coal, chalk, a nail, or even a sharp-edged rock. It was a survival code.

One morning I fished Willy’s slippers out from under the bed. When the hospital room’s heat failed, I gave him one of my blankets. “That blanket feels good,” he said, “like a warm piece a’ bread.” Suddenly in a reflective mood, he turned to me and with a weary grin, said, “For a white boy, you’re okay,” and proceeded to tell me what it was like to be a Black man who came north from Georgia in the 1930s.

In the South, he’d found work wherever he could, sometimes riding out into the countryside in a Model T with a root doctor, a skilled rural practitioner who used roots and natural remedies. But when steady work dried up, he did what hundreds of thousands did during the Great Depression: He hopped a freight train. Willy became a hobo, a footloose worker who took employment whenever and wherever he could. And when he couldn’t find it, he scrounged. And when he couldn’t do that, he went hungry, which was often.

Freight lines were a steel highway to ship goods through the U.S. Prior to the advent of the Interstate Highway System after World War II, the railroad was sometimes the only practical means of getting goods where they needed to go. Delivering hobos was a by-product. Trains were relatively easy to hop aboard when they slowed at switch points, long bends, and creaky bridges.

At the spurs—small railroads that lead into or away from factories, sawmills, lumberyards, and packing houses—the trains stopped. A hobo lingering nearby saw his opportunity and took it.

Which brings me back to the symbols. A hobo’s life was not all humorous rambling through the countryside, with baggy pants patched at the seat, a stubbly beard, and a pot of stew bubbling nearby. Hobos were often unwelcome. Farmers and small-town people were often preoccupied with their own survival. Sometimes, they had no time or patience for a man who said he was hungry and would work in exchange for food. The man could be legitimate, a thief, or a criminal on the run.

These strange symbols are the way hobos passed information on to the next guy (usually a guy, but as Willy pointed out, he did meet his first wife on the road). And as the chart below shows, hobos had a lot to say. They scratched out simple instructions about which direction to go or where’d be a good spot to catch a train, but the marks could also communicated elaborate details about the town (the police don’t like hobos here) or the homeowners (they’re an easy mark).

On that long-ago October afternoon, Willy told me about back-breaking farm work, long hot days and long cold nights. He had a small dog that kept him company and would even ride a hay rake with him when he found work on the many farms that dotted the countryside.

Some hobos were friendly, he said. Others were kooks, and some were dangerous scoundrels—or some combination thereof. The thing I’ll always remember from his first-person account: It was not an easy life, and romanticized versions of it are, at best, misleading.

Men like Willy filled me in on the specifics, and they left me awed by the hardships they survived. Willy went on to various gigs after his road-bound days were over. He owned and ran a lunch wagon that was a victim of sabotage. He settled on industrial work in Trenton’s many factories, which is how we crossed paths.

I didn’t have a chance to say goodbye. The way it happened, a nurse walked in and handed me my discharge papers while Willy was out getting X-rays. He returned to an empty room. We were like two men who briefly shared a box car, never to meet again.

Don’t Take My Word For It

If Willy Howard were alive today, he would be nearly 120 years old; since it’s unlikely that you’ll meet another Willy, your next best bet is to glean a first-hand account of long-ago hobos from an elderly person who encountered them as a kid. Lots of elderly people once lived in small towns and encountered authentic train-hopping hobos.

My friend’s father, for example, now a widower living in upstate New York, knew several hobos as a kid, growing up in a Maine lumber town. He turned out to be a pretty footloose guy in his own right. After some time in an orphanage and as a foster child, he walked out the kitchen door on his 18th birthday and never looked back. Instead of hopping a freight, he enlisted in the Army Air Corps. To this day, he fondly recalls the Maine hobos of his youth, men with colorful names like Axe Handle Pete.

Suppose you don’t know anybody as colorful as my friend’s dad. Your next best bet is to look around on the web. There’s a ton of fascinating information about hobos of the past and even current practitioners of the traveling art.

Can You Decode the Hobo Code?

Watch This:

Roy Berendsohn has worked for more than 25 years at Popular Mechanics, where he has written on carpentry, masonry, painting, plumbing, electrical, woodworking, blacksmithing, welding, lawn care, chainsaw use, and outdoor power equipment. When he’s not working on his own house, he volunteers with Sovereign Grace Church doing home repair for families in rural, suburban and urban locations throughout central and southern New Jersey.