Land, Limits

and the

Scandal of Reparations

Dr. Allan C. Carlson

We’ll call him Mr. Anderson. Featured not so long ago in The Wall Street Journal as his Kansas county’s leading farmer, the newspaper pointed to him as a model for the nation’s agricultural future.

Owning thirty thousand six hundred acres, a full ten percent of the county’s cropland, he bases his decisions on “a constant analysis of efficiency and scale,” featuring the use of ever larger and more sophisticated machines operated by hired labor. Mr. Anderson avoids the farm cooperatives inherited from an agrarian past for they are becoming, in his words, “just a place to drink coffee.” They are unable to change quickly enough “to keep up with the competition that can turn on a dime.”

Indeed, he can point to common measures of success. He owns a sprawling home just outside the county seat, vacation homes in Denver and Arizona, and another on a nearby lake. His hired workers draw a steady wage along with benefits and paid vacation.

Mr. Anderson constantly seeks to acquire more land, frequently stepping in at the last minute at farm auctions to outbid all others. To those asking, “haven’t you got enough, by now?,” his answer is vague: “There’s a reason behind continuing to accumulate,” he says, so that “everything carries on.”

In fact, he intends for that accumulation to transcend even his death. Mr. Anderson, age fifty-nine, has no wife, no children, or other heirs. He plans to put his agricultural property into a foundation which, he argues, would maintain jobs and fund local charities, while preventing his farmland from ever being sold to others.

The second person featured in the article shall be called here Mr. Young. Twenty-nine years old, he is married and has a toddler. Raised on a nearby small farm still operated by his parents, Mr. Young yearns to build one of his own: “For as long as I remember, it’s been what I wanted to do.” For the past five years, he has been renting small tracts of land to farm himself, using borrowed machinery. He hopes to earn enough cash to acquire land — and a mortgage — of his own, only to find himself regularly outbid by Mr. Anderson. “That’s aggravating,” he sighs, as opportunities come up only to go to “the big guys.”

The second person featured in the article shall be called here Mr. Young. Twenty-nine years old, he is married and has a toddler. Raised on a nearby small farm still operated by his parents, Mr. Young yearns to build one of his own: “For as long as I remember, it’s been what I wanted to do.” For the past five years, he has been renting small tracts of land to farm himself, using borrowed machinery. He hopes to earn enough cash to acquire land — and a mortgage — of his own, only to find himself regularly outbid by Mr. Anderson. “That’s aggravating,” he sighs, as opportunities come up only to go to “the big guys.”

The social result is a shriveling human presence. Alongside the struggling cooperatives, the local schools are losing pupils, a decline of twenty-five percent since 2000. More broadly, another county farmer notes, “the young people are moving away,” as technology steadily reduces the need even for paid human labor on mega-farms like Mr. Anderson’s.

This Journal essay actually underscores a profound truth about capitalism. Be it manifested in the factory, at the retail level, or on the farm, this economic system has no innate respect for limits. Instead, accumulation and growth are its imperatives, seemingly without end. In this regard, Mr. Anderson is like many other successful capitalists before him.

Now, if land ownership doesn’t really matter, if a decent wage is no different than gaining a living off the land, if farming is simply another occupation, and if a well-settled landscape is of no intrinsic value, then there is no problem. Mr. Young and his kind should either try to work for Mr. Anderson or join the exodus from the county to places with “more opportunity.”

Alas, the historical record and human wisdom teach that ownership does matter, not on the margins, but fundamentally. This is true both in terms of political economy and care of the land. Regarding the former, the late seventeenth-century philosopher John Locke was, in practice, an agrarian. He held that the ownership of property was the foundation of civil order, with the “chief matter of property” being “the Earth itself.” Farmland, woods, and other natural resources should be as broadly distributed as possible, for ownership gave men a stake in supporting a relatively free political sphere. Importantly, Locke also believed in limits here. The individual’s right to property required that “enough, and as good [be] left in common for others” and never exceed what the person could directly use.

Alas, the historical record and human wisdom teach that ownership does matter, not on the margins, but fundamentally.

As John Medaille has usefully noted, Adam Smith too was never the prophet of modern capitalism, as now widely assumed. Rather, he held in The Wealth of Nations [1776] that farming was “the Principal Source of the Revenue and Wealth of Every Country” and that merchants and manufacturers existed in effect to serve farmers, not the other way around. Moreover, he deplored monopolies such as would be found in Mr. Anderson’s Kansas county, favoring the dispersion of economic power.

Thomas Jefferson famously held to the same principles. He saw private property as “a corollary to democracy” for it enabled persons to achieve self-reliance, find economic security, and build a stable commonwealth with others. As he wrote in 1785 to John Jay: “Cultivators of the earth are the most valuable citizens. They are the most vigorous, the most independent, the most virtuous, and they are tied to their country and wedded to its liberty by the most lasting bonds.”

Indeed, modern research in the behavioral sciences confirms that “democratic property” favoring continuity rather than mobility is powerfully tied to community engagement and health. As summarized by legal scholar Thomas W. Mitchell, this has proven particularly true for working class and poor, minority communities, with important social consequences. At all levels, though, land and liberty remain tightly bonded. Writing in the Yale Law Journal in 1993, Robert C. Ellickson reaffirmed the agrarian postulate: “Compared to other resources, land remains a particularly potent safeguard of individual liberty. Like no other . . ., land can provide a physical haven to which a beleaguered individual can retreat.”

Land ownership is also important to care of the earth. Owning a renewing asset such as farmland nicely and naturally binds self-interest with social responsibility. Protecting the soil’s fertility contributes not only to current abundance but also to a legacy in land for those to come. Now in practice, this has not always proved true, for the American record is replete with tales of farmers who ruined the land they owned. Sometimes, this occurred out of ignorance over the basic methods of soil conservation. More often, perhaps, this came as a consequence of extreme economic pressures. Nonetheless, the incentives for good stewardship are vastly stronger when the farmer owns the land, rather than leasing or working on land belonging to others.

Such stewardship also demands proper scale. The old truth — “A farmer’s shadow is the best fertilizer” — and the practice of close, personal attention to one’s property works only on relatively small farmsteads.  For example, on the classic Midwestern family farm of one hundred sixty acres, the inhabitants can literally walk the landscape and come to appreciate variations in soil, plants, and animals both wild and domestic. Small ponds, groves of trees, fencerows, and prairie remnants require footsteps and welcome human touch. The farm thrives in a diversity of uses. In contrast, mega-farms must have massive machines that separate operator from soil and demand uniformity in the landscape. Fencerows, wetlands, and trees must go, to make way for the thirty-six-, or perhaps now the seventy-two-bottom planter. Variety is alien to efficiency.

For example, on the classic Midwestern family farm of one hundred sixty acres, the inhabitants can literally walk the landscape and come to appreciate variations in soil, plants, and animals both wild and domestic. Small ponds, groves of trees, fencerows, and prairie remnants require footsteps and welcome human touch. The farm thrives in a diversity of uses. In contrast, mega-farms must have massive machines that separate operator from soil and demand uniformity in the landscape. Fencerows, wetlands, and trees must go, to make way for the thirty-six-, or perhaps now the seventy-two-bottom planter. Variety is alien to efficiency.

The last eighty years have witnessed a related change in the common American understanding of land. Prior to 1940, and in harmony with the agrarian maxims of Locke, Smith, and Jefferson, land held unique value in and of itself. While surely an economic commodity, it was also a matter of great social, cultural, and political importance, attitudes to be found even in the old United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Since that year, however, the “new” view has given primacy to individual wealth maximization. Land no longer holds intrinsic value. It is merely one more “fungible commodity” whose value should be fixed solely by the competitive marketplace, and fully interchangeable with cash.

All of these themes and questions powerfully converged in recent decades over the record of black Americans’ historical relationship to land, and its application in turn to the explosive issue of reparations.

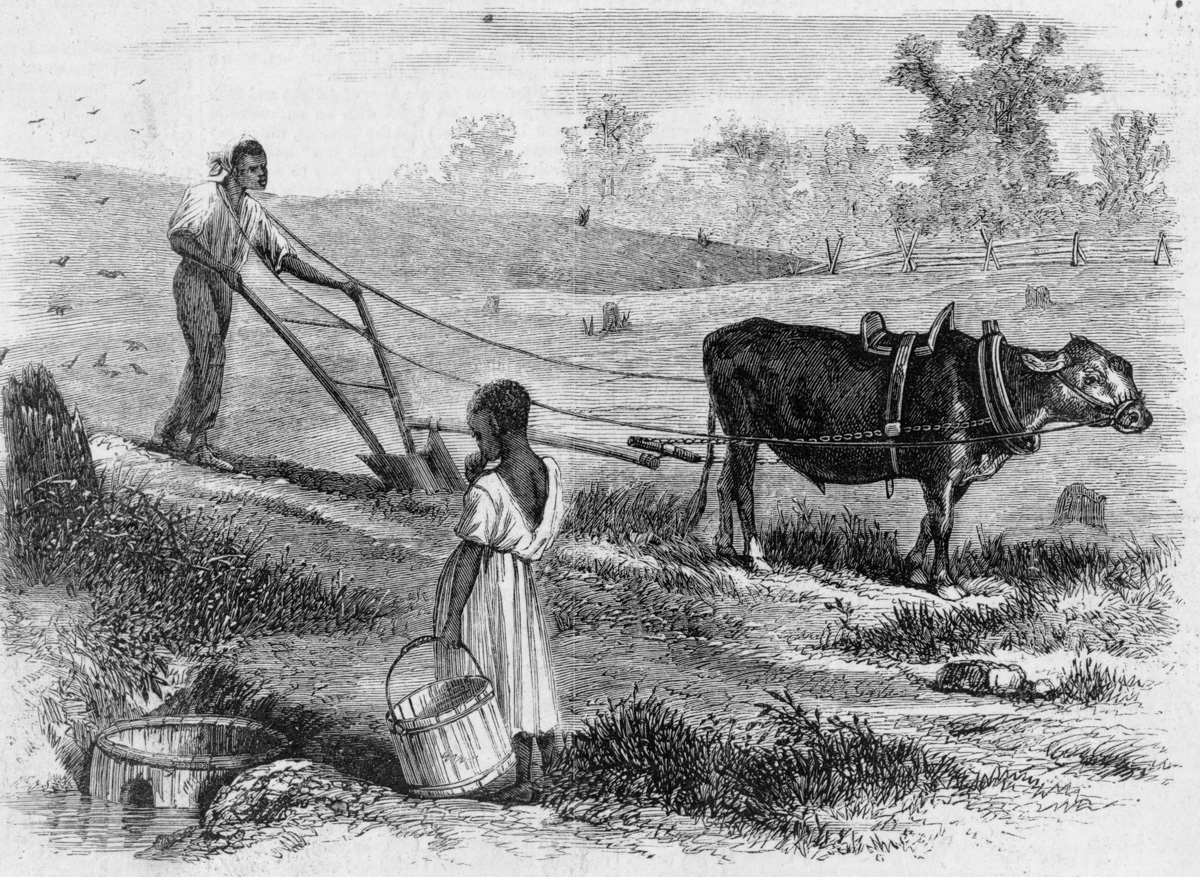

Some history should come in here. As the Civil War had drawn to a close, the fate of four million former slaves in the South hung in the balance. Startling, both then and in retrospect, was the “land imperative” they felt. Reliable reports indicated that gaining ownership of farmland was more important to them than gaining the right to vote. True liberty, they believed, would only come through property in farms.

The way forward seemed to appear on January 16, 1865, when General W.T. Sherman issued Field Order Fifteen. It declared the Sea Islands stretching from Charleston to Savannah to be “abandoned land” available for distribution to freed black families. Over the next few months, General Rufus Sexton settled forty thousand freedmen on forty-acre plots, also providing a surplus horse or mule as available. So was the promise of “forty acres and a mule” born. In March, the U.S. Congress established the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, promising all newly freed families forty acres of land at rental for three years, with an option to buy. The Southern Homestead Act of 1866 opened forty-six million acres of public land to freed slaves for settlement, at first on eighty acres, then one hundred sixty.

Both the Freedmen’s Bureau and the Southern Homestead Act proved to be abject failures. While the Bureau did hold eight hundred fifty thousand acres for distribution in its early months, half of even this modest amount was returned to former white owners by the end of 1866. More broadly, President Andrew Johnson reoriented the whole of postwar Reconstruction to favor white landowners and their heirs, in service to his version of reconciliation. Hopes for the most direct, just, and appropriate form of Reparations for slavery — provided in the form of land on or near where the slaves had personally toiled — so disappeared. The scandal began here.

Instead, most blacks in the South traded slavery for tenancy on quite unfavorable terms or, if they were lucky, for sharecropping, which at least provided some room for autonomous action. All the same, the Land Imperative remained strong. Despite the failure of Reconstruction, the rise of Jim Crow laws codifying segregation, lack of access to credit, and episodes of violence, blacks began to acquire land through private purchase. Between 1870 and 1910, this amounted to fifteen million acres. In that latter year, black owner-operated farms in the South numbered two hundred twelve thousand. Another six hundred seventy thousand black farm families worked on shares, with white owners providing cropland and blacks providing the labor and their own basic tools. Nationwide, one of every seven farms in the United States was black operated; in the South, one of every four.

Alas, by the year 2000, almost all of that was gone. Where the U.S. Census count of black farms in 1910 was 925,708, the number at the turn of the Millennium was a mere 18,451, a staggering decline of ninety-eight percent. Nationwide, fewer than one percent of farms now had black owner-operators. Taking the future into account, the number of black farmers under age thirty-five, again for the whole of the country, was only seven hundred forty-five, about the number that would fit into a large banquet hall. Virtually the whole black agrarian class had disappeared.

What had happened?

Part of the tragedy lay in extraneous causes. The outbreak of war in Europe in 1914 led to a collapse in the price of cotton, still the staple crop. The boll weevil, a pest out of Mexico which attacked cotton plants, crossed the Mississippi River in 1908, and wreaked another kind of havoc over the next two decades. Massive rains and severe floods followed in 1916. Many farm families simply gave up, and joined the Great Migration of blacks to the industrial cities of the North.

A second problem, this time afflicting black farms disproportionately, was—oddly enough—a broad failure in estate planning. For reasons not entirely clear, the black owners of farms proved significantly less likely to draft wills, which could leave farms intact for a single or limited number of heirs. On their deaths, instead, land passed into intestacy, where state laws mandate the division of ownership among family members by fixed ratios. This left the land under “tenancy in common,” a very unstable form of ownership which commonly resulted after a time in a forced sale of the property.

Land speculators and consolidators gained, while black family ownership and operation disappeared.

A third, and more disturbing, cause has been attributed to a form of discrimination within the Federal government. As found in the case Pigford v. Glickman, resolved in 1999, USDA officials and agents during the second half of the 20th Century routinely denied black farmers fair and equal access to credit, price supports, and other forms of assistance provided by the agency. The Court held that this had resulted in the frequent loss of farms to foreclosure. Under the consent decree, affected black farmers or their immediate heirs could receive a $50,000 cash payment.

An early estimate of the cost of this decision to the federal government was $2.25 billion, making it the largest civil rights case ever settled in this nation. When a second group of claimants came forward in 2009-10, some commentators on the political right were decidedly displeased. “PIGFORD May Be the Biggest Scam in American History,” declared Andrew Brietbart. “Reparations Have Begun.” Overall, thirty-three thousand claimants finally received a check.

While true wrongs may have been acknowledged here, the compensation in another sense was flawed. As one of the attorneys involved complained, “they didn’t get the land back.” Instead, the settlement adopted the modern view that farmland is merely another “fungible commodity,” interchangeable with cash. Moreover, the $50,000 was not enough to allow successful claimants of relatively advanced age—as most were– to re-enter farming. The real winners here, ultimately at taxpayers’ expense, were those who had bought up the foreclosed farms; in practice, they were overwhelmingly white. Judged against the standards of agrarianism and reparations, the result of Pigford was again failure, another kind of scandal.

The fourth and perhaps most consequential cause can again be traced to the federal government: an effort now of 80-years-duration to transform American agriculture into ever fewer farms. This has meant favoritism in everything from cash payments and sweetheart loans to research at federally funded universities that favor the Mr. Andersons of the nation. It has also meant the planned destruction of family-scale agriculture, be the farmers black, white, hispanic, or any other. The project has usually been veiled in platitudes about “progress” and “efficiency.” Sometimes, though, its managers have confessed the raw truth. It was Earl Butz, Secretary of Agriculture for Richard Nixon, who told farmers to “Get Big or Get Out.” In 2019, Sonny Perdue — Agriculture Secretary for Donald Trump — delivered the same message to desperate Wisconsin dairy farmers: “In America, the big get bigger and the small go out.” He continued: “I don’t think in America we, for any small business, have a guaranteed income or guaranteed profitability.”

Such declarations ring with a sense of inevitability. Behind the claims of the mega-farmers regarding progress, efficiency, and a free market, however, and behind their contempt for small business and cooperatives, lies the reality of federal farm payments. Of one sort or another, they totaled $47 billion in 2020 alone. All but a miniscule part of this has gone to that group that Mr. Young calls “the big guys.” This at least is not the result of an honest market designed to serve consumers, but rather the mark of a very nasty and deeply ingrained version of crony capitalism. As Mr. Perdue correctly observed, the system today does little for real family farmers. Yet it has behaved wonderfully for those able to make large campaign donations. Importantly, black Americans have been disproportionately affected primarily because they were “small holders,” family farmers, and not because of their race.

During the last year, these issues reappeared as both the debate over reparations heated up and the Biden Administration’s stimulus relief package included measures to aid “disadvantaged” farmers. Regarding the former, advocates for reparations emphasize the record of past failed promises, such as those already noted in this essay. To borrow a phrase, justice delayed is justice denied. Those opposed to Reparations argue that the debt for slavery was paid over one hundred fifty years ago through the lives of Union soldiers, that it is impossible to calculate any further debt now owed to the living after six or more generations have passed, and that new rounds of racial preferences would aggravate rather than heal divisions in the nation.

On stimulus aid, the Biden agenda has built on the Pigford precedent, providing an additional $4 billion or so to “socially disadvantaged” farmers of black and several other races and ethnicities, this time for payments worth one hundred twenty percent of their indebtedness on USDA farm and storage facility loans. Alas, like Pigford, this new infusion of cash does nothing directly to restore land lost, nor to encourage new settlement on the land by young families. And it does nothing important to challenge the cult of consolidation and bigness that rules the USDA. Predictably, given the measure’s focus on debt incurred in the past, the recipients are going to be — once again — the relatively old. Indeed, the primary black winners may well be in practice a comparatively small group of remaining big operators, “Mr. Andersons of color.” This emerges as the most revealing, and ironic, scandal of all.

So, what should be done?

The first task is broadly moral and intellectual: the recovery of a true land ethic. Holy Scripture can help here. The agrarian Wendell Berry, in an essay from four decades ago entitled “The Gift of Good Land,” holds that the Bible teaches “a proper human use of Creation.” He wisely passes over the Genesis command to the first humans that they “subdue” the earth, which is too easily misunderstood. Instead, he favors Genesis 2:15, describing how God placed the man in the Garden, “to dress it and to keep it.”

Moreover, Mr. Berry finds wisdom in the story of the Hebrew people’s relation to the Promised Land. It was not, he says, “a free or a deserved gift, but a gift given upon certain narrow conditions.” Absolute (or what we moderns call “fee simple”) ownership was not given. Rather, God declared that “the land shall not be sold forever: for the land is mine; for ye are strangers and sojourners with me [Leviticus 25:23].” He demanded a sabbath for farmland every seven years, where it might lie fallow and be renewed. And God ordained a Jubilee every fifty years, when cropland and fields would be restored to the original families. This social ethic also expects that those holding such land be faithful, grateful, and humble, that they be neighborly, and that they see land as an “inheritance,” with equal claims on it by those who came before and those who shall come after, as well as by those now living. In this way, land ownership becomes an expression of charity, a form not locked into a “foundation” but practiced daily by humans, face-to-face.

It was not, he says, “a free or a deserved gift, but a gift given upon certain narrow conditions.” Absolute (or what we moderns call “fee simple”) ownership was not given. Rather, God declared that “the land shall not be sold forever: for the land is mine; for ye are strangers and sojourners with me [Leviticus 25:23].” He demanded a sabbath for farmland every seven years, where it might lie fallow and be renewed. And God ordained a Jubilee every fifty years, when cropland and fields would be restored to the original families. This social ethic also expects that those holding such land be faithful, grateful, and humble, that they be neighborly, and that they see land as an “inheritance,” with equal claims on it by those who came before and those who shall come after, as well as by those now living. In this way, land ownership becomes an expression of charity, a form not locked into a “foundation” but practiced daily by humans, face-to-face.

Relative to the current situation, Scripture also wants limits. As Mr. Berry asks, “Does not Christianity imply limitations on the scale of technology, architecture, and land holding?” He answers in the affirmative, and praises the “earth keeping classes” — yeoman farmers and artisans — who understand and accept these restraints.

How might these principles be applied today? More specifically, how might they animate the effort to provide reparations for slavery in an agrarian manner, so restoring a meaningful black presence in American agriculture?

There may be a way . . . a Third Way. Most directly, one can look to the 1930s, when the New Dealers launched an effort to craft new agrarian villages among the rural poor. Called Subsistence Homesteads, federal agencies provided land for five acre family tracts complete with a new, modest house and small outbuildings, assistance in basic animal husbandry and gardening, and a community center. Ownership could be acquired on favorable terms. Perhaps the most famous of these was Granger Homesteads, northwest of Des Moines, Iowa. Guided by the local Catholic priest, Luigi Ligutti, Granger succeeded in providing land and security for fifty recent immigrant families from Italy and Croatia.

More relevant here was the Prairie Farms homestead project in Macon County, Alabama. Reserved for poor black families, it provides another example of success. As historians Robert E. Zabawa and Sarah T. Warren have reported, the thirty-four families settled at Prairie Farms shared livestock for breeding, created a community pasture for shared use, and purchased appropriate machinery on a cooperative basis. A new school built as part of the project became a center of community life, complete with a student cooperative, 4-H and nature clubs, and adult education in science and farming.

Rather than a throwback to pre-modern times, Prairie Farms was — in Zabawa and Warren’s words — “an exercise in the creation of a community based on change”: from tenancy to ownership; from cotton alone to diversified farming; from dependency on a plantation owner to cooperative buying and selling; from primitive schools to a modern high school; and from scattered cabins to good houses in a village setting.

Alas, the coming of World War II saw the federal government abandon support for and protection of villages such as Granger and Prairie Farms. Farmland consolidation, machinery in place of human labor, and suburbs with tiny lots instead of subsistence homesteads became the new governmental imperatives.

Farmland consolidation, machinery in place of human labor, and suburbs with tiny lots instead of subsistence homesteads became the new governmental imperatives.

Still, might not some version of the Homestead project, appropriately recast, return as an exercise in the long-deferred task of reparations for slavery and subsequent discrimination? New villages could be funded to include young, black homesteaders, with substantially greater tracts of land (one hundred sixty acres?) and direct grants for the purchase of appropriate machines, breeding stock, and seed. Ownership could be granted on the old 1862 Homestead model: after five years of residence on, and use and improvement of, the land.

From where would the farmland come? At first, existing public lands might suffice. However, if demand dictated and if the need for contiguous properties valuable to community health required, then eminent domain (with the usual compensation) could be employed. Some of the vast monopolistic farm complexes could so be broken up, for the benefit of new homesteaders. This no doubt will elicit some objections, but perhaps society can muster comparable resolve in addressing both our sin of slavery and the long-running policy assault on family farming as we do in addressing our need for a new shopping mall.

Skeptics might immediately respond that few, if any, young blacks would welcome such a regressive opportunity. Not true. Prototypes of black cooperative rural living and substantial interest by young blacks in a return to the land already exist. For example, Leah Penniman, author of the book Farming While Black, operates a school for “farmers of color” that already counts five hundred graduates, with a “long and enthusiastic waiting list.” Potential participants in a new black homesteading adventure would certainly number in the thousands.

The skeptics will then reply that such persons would nonetheless soon face the Mr. Andersons of the nation, and fairly quickly lose their land and their dreams to the inevitable process of consolidation by more efficient operators. The answer here has also been anticipated by Ms. Penniman: “You really need to look at land and wealth reform in a serious way.”

Indeed! As restated by Thomas Mitchell in the Northwestern University Law Review: “Even if discrimination is uprooted, policies designed to support all small farmers — white and minority — must be implemented in order to renew the prospects for small farmers who have not prospered under this country’s agricultural policy” during the last eighty years.

What might this mean? One task is to return to 1948, when American farm policy-makers rejected a most promising alternative. It was called the Brannan Plan. Proposed by the then U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, Charles F. Brannan, it built on existing policies of price supports for certain farm commodities. In doing so, it employed the concept of parity, where the USDA would make up the difference between a “fair” price measured against a bundle of non-farm goods and the market price.

Brannan’s proposal, though, involved still more radical changes. First, it would end most of the detailed restraints on the production of farm goods, which had been a staple of New Deal policy in the 1930s. Second, it expanded the list of commodities covered to include not only corn, wheat, cotton, and tobacco, but also whole milk, eggs, chickens, hogs, beef cattle, and lambs . . . with others to follow. Third, the plan would limit support only to farmers who practiced good soil and water conservation. And finally, price-support payments would be ended, or capped, at a level that supported a family-scale farm, but no more. Larger acreages could still grow whatever amount their owners chose, but the sale of such commodities would be entirely governed by the marketplace.

Brannan’s purpose was clear: USDA policy should do nothing “to encourage the concentration of our farm land into fewer and fewer hands.” Federal support would be reconfigured to embrace limits in farm size and stewardship of the land.

The plan drew the enthusiastic support of the National Farmers’ Union, known for its support of “full parity” and family-scale farming. However, the Farm Bureau—representing the Mr. Andersons of the time—fiercely opposed it as “socialist,” even “communist.” (In fact, the Brannan Plan was far more market-friendly than the then-existing policy tangle; yet the negative labels stuck.) Opponents objected especially to the cap on federal aid to any single farmer and to the conservation requirement. The plan died in Congress.

Going forward, why not bring back the principles of the Brannan Plan, reconfigured for the twenty-first century? Place a limit or cap on the amount of USDA assistance going to any single farmer. Require that recipient farms employ sustainable environmental practices and good stewardship of the soil. On related matters, favor again producer and consumer cooperatives and local rural credit unions. And redirect agricultural research at the universities to support diversified production. Put another way, end the massive subsidies that now flow to the mega-farms in this land, in favor of limits and care of the earth.

At the same time, the maintenance of a well-settled countryside should be declared a national priority. Then, take perhaps $10 billion a year of existing farm subsidies and redirect the money into grants and subsidized loans for land purchase by young families of any ethnicity seeking to found a new small farm: perhaps net support of $25,000 in the first year and $10,000 annually for the next four. They must responsibly maintain their homes and farmsteads, engage in animal husbandry and gardening, use sustainable farming methods, and open their property to reasonable visits by school children and similar groups.

Such policies would help restore a healthy human presence on the land. They would encourage a welcome diversity in American rural life, in natural, agricultural, and racial and ethnic ways. They would celebrate a respect for limits and stewardship of Creation, absent for far too long in this country. And they might — just might — help turn the question of reparations into a healing, rather than a divisive, idea.