[Editor’s Note: Here’s a fun post by one of my favorite people on the actual Day of the Dude (the anniversary of the film’s release date which is observed by adoring fans all over the world). It’s a great day to light a candle for the Coen Brothers.]

Let me explain to you something about the Dude.

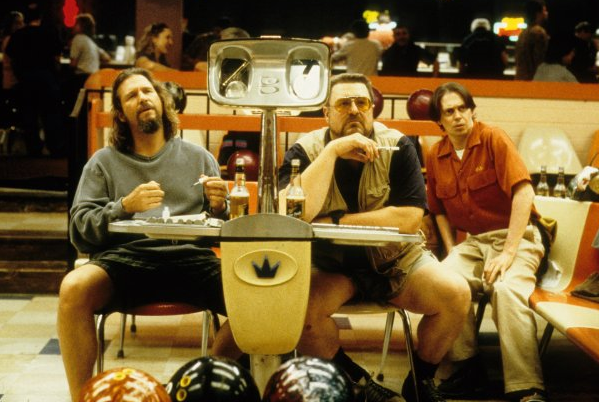

The Big Lebowski appeared in 1998 and enjoyed mixed commercial and critical success. Since then, however, it has gained a mighty cult following. Devotees quote the film incessantly. An annual convention calling itself “Lebowski Fest” meets every year in the U.S. A British counterpart calling itself “The Dude Abides” also meets annually. If you ever go to a bowling alley and see a guy wearing combat boots and shooting glasses, you can be sure he’s a Big Lebowski fan.

To most, the film is a farce depicting the misadventures of an aging 60s hippie, a frustrated military veteran, and, well, whatever Donny is. A closer look, however, reveals something more, namely a commentary on the current state of Western culture, at the time of our war with Saddam and the Iraqis, roughly the turn of the millennium–our time.

The movie centers on a strange episode in the life of Jeffrey Lebowski, known at his own insistence as “the Dude.” Today “dude” is used to indicate something like “guy,” or “man,” as in “generic male person.” In its original usage “dude” specified humanity in a particular context. It was first used by western cowboys in the 19th century to describe someone from the eastern U.S. who didn’t fit in. It was slightly derogatory as the cowboy narrator suggests at one point – “that’s a name no one would self apply where I come from.”

The ubiquity of the Dude’s favorite drink further identifies him with the West. His drink of choice is the “White Russian,” which he refers to as the “Caucasian.” The Caucasian is the man of Europe, Western man, that subset of humanity that moved west across Europe, the Atlantic, and finally across the Americas to settle as far as it could reach, California. In other words, in Jeffrey Lebowski we get a picture of the state of Western man. “He’s the man for his time and place… fits right in there.” All told, the assessment provided by the movie is absurdly, albeit comically bleak: the West is God-less and spiritually bankrupt, or put philosophically, Western man is a nihilist.

One familiar with the film will object: “The Dude is not the film’s nihilist; the Germans, led by Uli, are the nihilists.” But such an objection betrays that one’s thinking about this case has become very uptight. It fails to recognize the clever irony employed by the screenwriters. In a movie of wildly different characters – the Dude, Walter, Maude, Bunny, the big Lebowski – each of whom could not seem more different from the rest, the characters known as the Nihilists still manage to seem uniquely bizarre.

But just as a person insisting on his own innocence too much will only make himself look guilty, the repeated insistence on the nihilists’ uniqueness may be the storytellers’ way of pointing to a fundamental quality shared by all the characters. All of them are nihilists.

The nihilism of the characters is signaled in what may be the movie’s funniest aspect, the characters’ relentless imitation of one another. “This aggression will not stand.” “The Chinaman is not the issue here.” “In the parlance of our times.” These phrases get up in the air, and are inhaled and exhaled by all the characters, seemingly without their realizing it. It is as though all of them are hollow, and echo back to each other all that each other says.

By its very nature imitation is a tendency towards sameness, and as imitation continues, imitators increasingly resemble one another. This generates for each character an ironic relationship with all others. They despise one another, look down upon one another, mistrust one another, and are generally baffled by one another’s mannerisms and expressions, but all the while their reflexive mimicry of one another produces in all of them a thoroughgoing sameness.

The Dude’s reflexive mimicry reaches a kind of crescendo in the final confrontation with the big Lebowski, which brings the movie full circle. The Dude demands, “Where’s the money Lebowski?” This is the very same question one of Jackie’s goons asks the Dude as he forces his head into a toilet in the opening scene of the movie. And in a final ironic twist, we discover that the nihilists are not so nihilistic after all. In their final appearance where they confront the Dude and Walter about their money, one of them complains that it is only fair that they should get the money for which their girlfriend “gave up her toe.” The nihilists are unprincipled and self-absorbed, just like everyone else.

Can anything raise the characters above this morass? Does the “Stranger” offer any hope? As his name suggests, the Stranger seems oddly “other,” narrating the story and dialoguing with the Dude from what seems beyond the strict limits of time and space. He promises at first to be a kind of conscience for the story, especially for the Dude. And yet, in the end, we see that he too is spiritually empty. His grand statements trail off into incoherence, and once his advice to the Dude to clean up his language is rejected, he immediately quiets himself. As it turns out, he is not “strange” enough to offer anything truly different from what we see in all the others.

We see too that the West’s religious traditions have grown too weak to lend substance to the characters. The meek and lowly Jesus of the Gospels seems worlds away from the character Jesus Quintana, but the conflict between him and Walter corresponds, even if only in the barest of outlines, to an essential aspect of the Gospels’ narrative: the conflict between Jesus and the Pharisees concerning Sabbath observance (Mark 2:27). This conflict and the larger narrative of which it is an essential part came to inform the moral sensibilities of the West. Here we see it has atrophied nearly beyond recognition.

Walter’s Judaism seems at least slightly more robust than Quintana’s Christianity. He is heard to quote the Jewish philosopher, Theodore Herzl. At various points he quotes from the book of Proverbs – etz chaim hi: “she is a tree of life” (3:18). At the end of the movie, however, when Walter begins to extemporize a eulogy for Donny, he quickly strays from the subject of Donny and his eternal destiny, and lapses into yet more reminiscences of his Vietnam War service. It seems that the Dude is right that Walter’s Jewishness is a part of his “sick Cynthia thing,” referring to the ex-wife for whom Walter converted to Judaism in the first place.

It may be that Donny’s destiny indicates a prospect for Western man that is to be feared. In a sacrificial gesture as confused as his Judaism, Walter attempts to pour out Donny’s mortal remains “into the bosom of the Pacific Ocean.” But this last westward movement is aborted by the wind, and in a kind of “Ash Wednesday moment,” Donny ends up scattered on the beard and sunglasses of the Dude. The movement West, or more importantly, the vital forces that made that movement possible, seem to be petering out. The Dude abides, as we hear, and a “little Lebowski” is on the way. The “whole durned human comedy keeps perpetuatin’ itself,” but only barely, almost in spite of itself.

The Little Lebowski that is on the way is destined to grow up in Maude’s world, a world described pretty well by the “Qué ridículo” we hear her speak into the phone at one point, which is accompanied by inscrutable and frenzied laughter. We don’t know where his ultimate destiny lies, but we see the considerable obstacles he faces. But as John Paul II in his Theology of the Body points out, the first guide he has is the first guide anyone has, and it is right at hand for him. It is in his own personhood and in his origin in the coming together of man and woman. The Little Lebowski’s origin is fractured and obscured by the disorder of the persons and culture around him, but the Gospel and the mystery of Christ and the Church, the story of the love of the bridegroom for his bride, will help him see, God willing, what he must behold first “through a glass, darkly.”

***

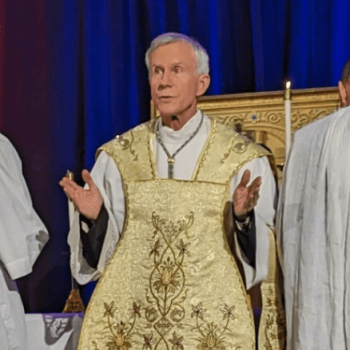

Fr. Michael Darcy is a priest of the Oratory of St. Philip Neri in Pittsburgh, PA.