On a Sunday afternoon in early September 2014, Sister Bernadetta Boggian drove into the compound of the Catholic convent where she lived in Bujumbura, the capital of Burundi, and called out to her fellow nuns. There was no sign of the other elderly sisters who lived in the convent, so Sister Bernadetta went to find Father Mario Pulcini, the head of the mission, to ask if he had seen them. He tried phoning them, but there was no reply. So they walked across the shady compound to the nuns’ quarters, where they found the curtains drawn.

They knocked, and called out, but there was no answer. The priest was about to force open the door, but Sister Bernadetta walked around to a side entrance, which was unlocked. Inside she found a horrific scene. Sister Olga Raschietti was lying dead in her bedroom, blood pooling around her head. In the bedroom next door lay the body of Sister Lucia Pulici. Both women had been stabbed, and their throats slit.

Sister Lucia would have celebrated her 76th birthday the next day. Sister Olga was 82. Together, these three elderly friends had worked for almost 50 years in South Kivu, an eastern province of the Democratic Republic of Congo that was at the centre of a series of conflicts sometimes known collectively as the Great African War, the deadliest in the continent’s modern history. When the three sisters finally left South Kivu for Burundi, they were looking forward to a more peaceful retirement posting.

Father Mario called the local police, and his superiors in Italy. Lorries and pickup trucks arrived quickly, disgorging police and soldiers, and security forces circled the compound. At around 6pm, the congregation poured out of mass in their brightly coloured Sunday best, straight into a crime scene. A papal official stood over the bodies and wept. Outside the convent, young women the sisters had taught to sew wailed with grief.

Sister Bernadetta, who remained collected throughout, accompanied the bodies to the morgue, and then returned to the convent. Father Mario wanted to find somewhere else for sister Bernadetta and the other nuns to sleep. But the sisters insisted they wanted to stay together, and sleep at the convent. As night fell, heavily armed police patrolled the compound.

When noises woke Sister Bernadetta during the night, she telephoned Father Mario, who was still awake, writing down an account of the previous day. “I think the killer is still here,” sister Bernadetta told him in a shaky voice.

The priest hurried to the nuns’ quarters, but he was too late. Sister Bernadetta was already dead. In an act of violence unimaginable to those who knew the small and wiry 79-year-old, the killer had cut off her head.

The next morning, shocked and angry locals closed their businesses and gathered outside the convent to protest against the murders. People claimed the killers were being protected by the police. Some protesters saw the notorious head of the state intelligence agency, General Adolphe Nshimirimana, enter the convent. Some time later, Father Mario emerged from the gates and appealed to the protesters to disperse peacefully. Three weeks on, a leaflet was found at the convent urging the mission not to pursue an investigation into the crimes.

The murders at the convent horrified Burundians, not just because of their brutality but because they took place almost a decade after the end of the country’s 12-year civil war, in which 300,000 were slaughtered and 1.2 million – a fifth of the population – fled their homes. In the wake of that conflict, which divided the nation along ethnic lines, between Hutu and Tutsi, Burundians vowed that their country would never again experience such brutal violence.

Church missions to countries riven by long-term civil strife are liable to get caught up in toxic politics. The powerful Catholic church in Burundi, which represents 80% of Burundians, has come under suspicion for providing aid to militant groups during the civil war. But it has also regularly criticised government abuses, and paid a price for it. In 1995, during the civil war, when the majority Hutus rose up against the abusive Tutsi military, gunmen executed two priests and a lay preacher suspected of supporting the rebels. A year later, a moderate Tutsi archbishop was murdered by gunmen. More than 10 Catholic clerics were assassinated in Burundi in the first three years of the civil war. When church leaders have denounced the violence of the country’s warring factions, political leaders have often seen them as a threat – and done whatever was necessary to silence them.

The murders at the convent followed a ripple of unrest across the region. In April 2014, the United Nations envoy to Burundi had cabled UN headquarters in New York with a warning that the Hutu-led ruling party was distributing weapons and uniforms to its youth wing. In some areas, particularly outside the cities, the group acts “in collusion with local authorities and with total impunity”. It acts like a “militia over and above the police, the army, and the judiciary”, the cable said. The group was described as “one of the major threats to peace in Burundi and to the credibility of the 2015 elections as they are responsible for most politically motivated violence against opposition”. The government of Burundi issued a rebuttal to the UN, vehemently denying that it had been funding, arming or training the youth wing, known as the Imbonerakure. Nonetheless, the cable was received with alarm.

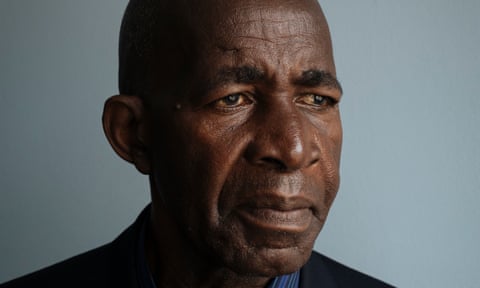

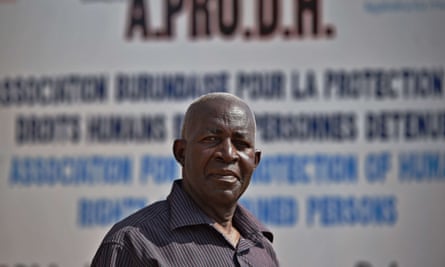

A few weeks after the UN cable, Burundi’s most prominent human rights activist, Pierre Claver Mbonimpa, told listeners of the popular radio station Radio Publique Africaine (RPA), that arms and uniforms were being given out to hundreds of young men, who had gone for military training in the neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Mbonimpa described photographs he had seen of young Burundian fighters training in the DRC, and first-hand accounts he had heard from witnesses and former soldiers. During the civil war, Mbonimpa’s own mother, a Tutsi, had been hacked to death by Hutu youths armed with machetes. A decade later, he pledged to do what he could to stop what appeared to be the preparation of a new youth militia. “In my experience, it is always the youths that do the killing. Everywhere in the region, it’s the youth that are used for violence,” Mbonimpa told me earlier this year.

In the hot and humid city of Bujumbura, on the shore of Lake Tanganyika, the poor live in airless, dusty and tight-knit grid systems, clustered around the centre and to the north. These poor neighbourhoods, particularly Kamenge, where the convent stands, had been fertile recruiting grounds for rebel groups looking for young men during the war. Once again, it seemed the youth were being prepared to fight.

People were afraid of what the training of this new secret youth army might mean. In a bid to end the civil war, a peace deal had been tabled in 1998 by president Julius Nyerere of Tanzania. Talks had continued under Nelson Mandela and his successor, Thabo Mbeki. An agreement was eventually signed in 2000, which laid out rules for equal representation of Hutus and Tutsis, and said that no president could serve more than two terms. A ceasefire finally became law in January 2005. As the 2015 elections approached, critics were afraid that Burundi’s president, the former Hutu rebel leader Pierre Nkurunziza, would try to hold on to power. Government forces and their opponents were preparing to face off in a new round of violence and intimidation. The president’s supporters insisted his rule brought peace to the country, and regeneration to the rural economy - he is passionate about growing avocados. His office maintained that a third term in office would be legitimate, as the first term (the result of an election by parliament, not the people) did not count.

Mbonimpa is a tall and powerful man, with a gentle manner and an unshakeable determination. Only the dusting of grey stubble on his head gives away his age. At 71 – in a country where life expectancy for men is 58 – he is considered one of the grandfathers of postwar Burundi, celebrated for his tireless work in exposing attacks on human rights workers, opposition politicians and journalists, enforced disappearances, illegal detention and torture. His work has earned him a loyal support base. In September this year, Human Rights Watch honoured his work with the Alison Des Forges award, given to leading campaigners for justice, describing him as “a man of extraordinary courage who has defied repeated threats to defend victims of abuse”.

Mbonimpa spent two years in prison during the war. Between 1994 and 1996, he was an inmate at the vast and overcrowded Mpimba prison, accused of a crime he did not commit. There, he was beaten and starved, he witnessed young boys locked up and abused by adults, women raped by guards and children born as a result. He emerged determined to reform the prison and justice systems in Burundi. Soon after his release, he founded the Association for the Protection of Human Rights and Detained Persons, now the most prominent human rights group in the country. He has secured the release of thousands of young Burundians who have been wrongfully imprisoned.

The day after Mbonimpa’s radio appearance, police called him in for questioning. They summoned him repeatedly over the next week, each time demanding that he reveal his sources – but each time, he refused. At midnight on 15 May, when he arrived at the airport for a flight to Kenya, a number of police officers were waiting for him. He had just enough time to call his wife before the police bundled him into a waiting car. At the end of the following day, Mbonimpa was indicted for “endangering the internal and external security of the state”, based on his comments in the media, and jailed once again.

When Mbonimpa was arrested in May 2014, four months before the nuns were murdered, a weekly protest known as “Green Friday” began in Bujumbura – with Burundians wearing green, the colour of prison uniforms, to show solidarity with Mbonimpa. Activists around the world joined in, tweeting photographs of themselves wearing green. His popular following infuriated the authorities, and radio stations were banned from reporting on the training and arming of militias.

But Mbonimpa had a surprising protector.

As commander of the ruling party’s military wing, General Adolphe was hated and feared by those outside his circle, but revered by his own men. At 50, he looked young for his age, sporting a moustache and wearing a heavy gold chain. A photograph popular with his followers shows him in a white baseball cap embellished with a gold eagle, the symbol of the CNDD-FDD, the Hutu rebel group that now runs Burundi. (The party’s full name translates from the French as The National Council for the Defence of Democracy – Forces for the Defence of Democracy. The repetition, Burundians joke, is just in case people need convincing their country is a democracy.)

The general owned a bar in Kamenge called Iwabo W’abantu, meaning “the home of the people”, just a few blocks away from the convent where the nuns were killed. A grandiose stone eagle marks the entrance. Inside, on a high shelf, a nervous monkey twitches in a cage. CNDD-FDD supporters and civil servants sit behind huge bottles of Primus, the local lager, and talk politics while nearby a crocodile basks in a dirty pond. “The home of the people” is rumoured to double as a torture chamber for dissidents – one of many said to be hidden across the country.

Adolphe, as he was generally known, was “not an educated man”, a former colleague said, but he was a gifted mobiliser, a man of the people. Generous and gregarious, he would stay up buying rounds of drinks until he was the last man standing. The Imbonerakure were largely made up of former Hutu rebels from the civil war and the general was like a father to them. During the civil war, he was a hero on the streets of Kamenge, the bastion of the Hutu rebellion.

After the war, Adolphe forged ties with a violent rebel group in the DRC formed by the remnants of Rwanda’s genocidaires. The UN reports that he used these ties to carry out large-scale gold smuggling from rebel-controlled mines. By 2014, people said that it was not President Pierre Nkurunziza, but Adolphe, his loyal and trusted lieutenant, who held the levers of power. According to Gervais Rufyikiri, the former vice president, who fled Burundi in June 2015, every decision in government first went past the general. After the peace agreement limited the president’s term of office, it was rumoured that Adolphe was training a private army to keep the president, and himself, in power.

As a human rights activist, Mbonimpa’s work involved challenging the brutality of Adolphe’s secret police – but the two men had a shared history. Mbonimpa was among the civilians who had supported the armed rebel movement during the war, providing food, information, money, and, occasionally, a place to hide, and General Adolphe was indebted to him for this. Mbonimpa’s own son was a rebel recruit. When Mbonimpa spoke out against the training of the Imbonerakure, he threw himself into direct conflict with the general, but he was confident that the general’s esteem would protect him. Adolphe had once told his son that if anyone killed Mbonimpa, the general would avenge him with his own hand – a vow that gave Mbonimpa courage to continue with his campaigning work.

But when Mbonimpa found out that the three nuns had been butchered with machetes in the trademark manner of Adolphe’s intelligence agents, the two men were once again set on a collision course – one that would threaten both their lives.

On 9 September, two days after the murder, the police arrested a local man named Christian Claude Butoyi and charged him with the nuns’ murder. Police told journalists that it was a revenge killing: the church had stolen Butoyi’s family land decades earlier, and bitterness at this injustice had driven Butoyi to rape and murder the nuns. Land disputes are common in Burundi – a tiny country with a barely functioning judicial system and one of the fastest-growing populations in the world – and are commonly resolved with violence. But Butoyi, 33, said nothing as police paraded him, handcuffed and dressed in ripped sports clothes, before the press. He showed no sign of remorse. Indeed, he showed no sign of any emotion at all. Residents of Kamenge recognised Butoyi as one of “les fous”, the mentally ill people who lived on the streets, surviving on scraps and charity – they doubted he possessed the physical or mental strength, never mind the motive, to carry out a series of brutal murders.

From his prison cell, Mbonimpa watched this farce unfold. It was clear to him that Butoyi was not the killer. The following week, a court freed Mbonimpa after four months in detention, on medical grounds – he is diabetic – but he remained under judicial supervision. A thousand-strong crowd gathered outside the court, singing and dancing in celebration.

When the authorities fail to deliver justice, Mbonimpa told me, it falls to journalists and human rights campaigners to discover the truth. To find out who was behind the murder of the three nuns, Mbonimpa approached one of Burundi’s leading investigative journalists, Bob Rugurika, the head of Radio Publique Africaine. The station, which broadcasts under the slogan “The Voice of the Voiceless”, was set up in 2001 with money from the Soros foundation; Samantha Power, US ambassador to the UN, was on the board. RPA’s goal was to heal the ethnic divisions of the civil war by getting Hutus and Tutsis to share airtime. There were one or two presenters who had managed to get members of militant groups to confess to killings on air – and express their remorse. A public confession could lay the foundations for reconciliation.

A small, energetic man, Rugurika joined RPA while he was at law school, and had become editor in 2010. His career has been split between revealing corruption and living with the consequences, which have included death threats and periods spent in exile.

While Mbonimpa was in prison, he had learned that as many as 1,800 members of the Imbonerakure had returned from the DRC and spread out across the country, ramping up their campaign of violence. On General Adolphe’s orders, the young fighters beat up suspected opposition candidates, disrupted meetings, and spread fear through the population.

Mbonimpa found a source close to the investigation who had been assigned to the nuns’ murder case – whose identity remains protected. The source reported that police officers guarding the compound had allegedly confessed to complicity, while four men had carried out the killings. They all claimed to be acting on the direct orders of officers loyal to Adolphe.

The police made a number of arrests based on these statements – but a few days later, Adolphe intervened. He ordered the suspects’ release, and the investigation into the nuns’ murder went no further.

In October 2014, at a secret meeting, Bob Rugurika was introduced to a former intelligence agent known as Mwarabu, or “the light-skinned one”. Over a number of meetings in darkened bars, parked cars and private houses, Rugurika won the trust of Mwarabu, who eventually confessed to taking part in the murders.

He even agreed to let Rugurika record his confession, on the condition that it could not be broadcast until he had fled the country. Mwarabu spoke into Rugurika’s microphone, and confessed that he and three others had killed the nuns, on the orders of General Adolphe.

According to Mwarabu, the nuns had seen the Imbonerakure training near their former mission in the DRC. When Adolphe had heard Mbonimpa on the radio saying that the youth militia was being re-armed and trained, the general was convinced that the nuns had been Mbonimpa’s secret source. After Mbonimpa’s arrest, Adolphe worried that the nuns would speak out in order to secure his release – and he knew enough about the courage of these elderly missionaries to understand that they, unlike many others, would be unafraid to testify against him.

The nuns had some additional inconvenient information, Mwarabu said. The former parish leader had been a legend among Hutus for surviving the 1995 massacre of Catholic priests, and a close ally of Adolphe. The general had used the mission’s health clinic to stock a private hospital he owned in the neighbourhood, to avoid paying import tax on drugs. In mid-2014, the parish priest became seriously ill and left Burundi for treatment in Italy. When the nuns and father Mario found out about the abuse of church resources, they were determined to put a stop to it. (The mission did not wish to comment on these claims.)

A month after he won the trust of one alleged killer, Rugurika was introduced to another, Juvent Nduwimana, in a bar. Juvent, who grew up in Kamenge, was a rebel during the war and later became an intelligence agent working for Adolphe. Rugurika recorded his statement at the RPA office, and Juvent stated on the record that the nuns had been silenced to prevent them revealing the existence of an armed militia being trained by Adolphe to keep the president in power.

In January 2015, the country came to a standstill at 12.30pm every day for a week as Bob Rugurika broadcast Mwarabu’s confession in a series of daily programmes on RPA. The streets fell silent as taxi drivers, traffic police, and street vendors gathered around radios to listen to the shocking admission of guilt.

Rugurika had planned to broadcast his interviews with Juvent as corroboration – but before he could do so, Rugurika was arrested on 20 January. Two days later, although he had not been charged, he was transferred to an isolation cell and denied visitors. The arrest outraged human rights groups. Mbonimpa addressed journalists outside his office: “They can imprison us, they can kill us, but they can’t shut us up,” he said.

Burundians took to the streets again in protest. Mwarabu, the confessed killer, sent Rugurika a message of solidarity from his hiding place in exile. A month later, a court freed Rugurika on bail, and thousands lined the streets in celebration.

Rugurika broadcast Juvent’s confession in full on 30 March 2015. In the recording, Juvent’s voice was quiet – he sounded nervous – but his account was detailed and damning. He had heard from his recruiting officer that Adolphe was concerned that news of the Imbonerakure training in Congo would spread. The Catholic order to which the nuns belonged, the Xaverian Missionary Sisters of Mary, also ran a clinic in Luvungi, South Kivu, close to where the Imbonerakure were training. The soldiers had been getting treatment at the clinic, and the nuns, who travelled frequently between Bujumbura and the eastern DRC, were aware of this. Adolphe’s main concern was to stop them talking.

The interview with Juvent was even more explosive than Mwarabu’s initial confession – since it corroborated the first confession, and pinned responsibility directly on Adolphe. Rugurika began sleeping in a different safe house every night – informed, by reliable friends, that security forces now had orders to kill him on sight.

In the weeks following Rugurika’s broadcasts, as fears of a return to civil war grew, more than 10,000 Burundians fled to neighbouring countries, a number that has since risen to around 296,000. There were reports of opponents being intimidated or dragged out of their houses and beaten.

On 25 April 2015, the ruling party announced that its candidate would be the incumbent Pierre Nkurunziza. For the third time in 12 months, thousands of men and women took to the streets, but this time they faced loaded guns. On the first day of the street protests, police shot dead at least one civilian. Armed men forced entry into RPA’s green-painted building and shut down all broadcasts. Observers watched with mixed feelings as Tutsis and Hutus united on the streets in defence of their hard-won peace agreement. A week later, Rugurika fled into exile, in fear of his life.

When President Nkurunziza flew to Tanzania to discuss the crisis with regional leaders on 13 May, news of a coup led by a senior general was broadcast on independent radio stations. The president was unable to return to the country after rebel soldiers took control of Bujumbura airport. General Adolphe, however, remained in Bujumbura, standing by to launch a counter-attack against the coup plotters.

State security forces attacked media buildings, throwing grenades at the headquarters of the Renaissance TV station. Flames licked the facade of the RPA building. Journalists who had stored sensitive evidence at the radio station, believing it to be the safest place, watched helplessly as years of their work went up in smoke. After dark, there was fighting in the streets, and bomb blasts shook the buildings. The next day, dead soldiers lay in the streets. No one knew who was in charge.

Later that day, news trickled out that the coup had failed. The government branded the coup’s plotters as terrorists, and launched a violent crackdown.

As journalists, politicians, activists, indeed anyone who might be perceived as anti-Nkurunziza, fled, Mbonimpa dug in. “I have no fear,” he told me in his office on 15 June 2015. In the previous six weeks, 94,000 people had fled. Ragged-looking men and women waited outside his office, either to report a crime or beg for news of a lost loved one. Mbonimpa had documented 77 dead (a figure that would later rise to more than 500) and 300 injured, but hundreds more – mainly young men – had disappeared.

Soon after RPA had broadcast the testimony of Juvent, the alleged second killer, at the end of March, Juvent was arrested. As police drove Juvent away, Mbonimpa followed in his car, in a dogged attempt to show they could not kill him, nor force him into changing his story about the nuns’ deaths.

President Nkurunziza surprised no one by winning the presidential election on 21 July. But his victory was far from peaceful. That night, blasts and gunfire resounded through the capital.

Less than two weeks later, early on a Sunday morning, General Adolphe was driving through Kamenge, accompanied by his bodyguards, when four men in fatigues ambushed their armoured black SUV. The gunmen launched two rockets at the vehicle, fired automatic weapons and lobbed in a grenade to ensure there were no survivors. Neither the rebels nor the ruling party claimed responsibility for killing Adolphe – although it was rumoured that his position as the head of the party’s militia made him a threat to its political leaders. One former ruling party politician in exile in Brussels said, “Adolphe had raised an army, and they became more important than the police, more important than the army itself.”

At the time, Mbonimpa was in the capital, Bujumbura, assisting African Union (AU) observers in their investigation of the illegal distribution of arms in Burundi. He remained at work, although he knew that with Adolphe’s assassination, he had now lost his protector.

The day after Adolphe’s death, at 5.30 in the afternoon, Mbonimpa said farewell to the AU delegation and got into his car. The driver took the road north through the city towards his home. At 6pm, two men on a motorbike pulled up alongside Mbonimpa’s car, and the passenger fired four times at his head. He lost consciousness for a few minutes. When he came to, he gave clear instructions to his driver, who was unhurt: “Take me home. I want to die with my family around me.” When they got to his house, his wife took one look at him and told the driver: “Take him to hospital.”

They raced to the Polyclinique Centrale in Bujumbura. Doctors stabilised Mbonimpa, and after a week he was flown to Brussels and was admitted to University Hospital. For four months, his head was clamped in a metal cage, and was fed by an intravenous drip.

But the attackers were not done with Mbonimpa. His daughter was forced to leave Burundi after getting death threats. In late September, her husband was murdered by men on motorbikes as he arrived at the gate of his home in Bujumbura.

On 6 November 2015, police in Bujumbura were searching the centre of the city looking for dissidents, when they tracked down Mbonimpa’s 28-year-old son, Welly Fleury Nzitonda. Seeing the police, he tried to run but they caught him. Hours later, neighbours found his body. He had been shot in the head and heart.

Mbonimpa, unable to attend his young son’s funeral, sent a note from his hospital bed for a colleague to read out after the burial. “Do not lose courage,” the note said. “The tragedies we face will end with a resolution of the conflict … I maintain hope that it will come soon.” Sitting in a fifth-floor temporary office on a grey day in Brussels on 10 May this year, recalling how he missed his son’s funeral, Mbonimpa wept.

On 9 December 2015, after four months in a head brace, Mbonimpa was sent for a scan by his doctor. Afterwards, he took a seat in the doctor’s office. The doctor looked at Mbonimpa for minutes without saying a word, then called in his colleagues. Six of them analysed Mbonimpa’s latest scan, and were amazed at his recovery.

After they removed the brace, the doctor asked: “Pierre Claver, what angel is it that walks with you? Even if we don’t believe in God, we have to believe in something because you, sir, have an angel that guides you every day.” Hours later, Mbonimpa walked out of the hospital with his wife, weighing just 56kg, but determined as ever.

In March 2016, the government alleged that a member of the opposition had ordered the nuns’ assassinations to tarnish the Burundi government’s reputation. Young rebels who trained in Rwanda carried out the killing, a government spokesperson said. “There was no Imbonerakure trained in South Kivu. So there was no need to cover up,” the spokesperson said, adding that Adolphe, a devout Christian, could not have been behind the assassination of members of a religious order. The spokesman blamed the crisis on the meddling of Rwanda in Burundi’s affairs, and on the international media, for fanning the flames.

Earlier this year, the international criminal court in the Hague announced that it would conduct a preliminary investigation into the violence that accompanied the re-election of President Nkurunziza in 2015. But the government of Burundi responded in October by announcing that it would simply withdraw itself from the court’s jurisdiction – “so we can really be free,” in the words of Gaston Sindimwo, one of Nkurunziza’s two vice-presidents. Other members of the AU have also withdrawn, claiming the ICC unfairly targets African countries.

“The day I feel well, I will return to my country,” Mbonimpa told me in March this year. Last month, the government revoked the licence of Mbonimpa’s human rights organisation, claiming it was responsible for destabilising the state. For now, he remains in exile.

Main picture: Phil Hatcher-Moore