Americans like things big. Big like Texas, big like the rolling Mississippi, big like the heaviest made-out-of-butter cow sculpture. They also like things with big meanings, like the Declaration of Independence, D-Day, and the driving of the golden spike to join the rails of the first transcontinental railroad, connecting the Central Pacific and Union Pacific lines on May 10, 1869 at Promontory, Utah.

The 150th anniversary of that unifying event recently took place, and the commemoration welcomed a merging of that metaphorical big with the literal: the return to service of one of the most heralded—and biggest—locomotives of all time.

The steam-driven locomotive might seem like a relic of bygone days, but tell that to the people cheering all the way to the clouds when the Big Boy 4014 pulled into Ogden for the Golden Spike ceremony, a steaming nova among other star locomotives.

Big Boy’s journey wasn’t an easy one; its roaring up the ceremonial rails seemed an improbable gamble, considering that all eight existing units (of the 25 built for Union Pacific) of the Big-Boy-class steam engines had been decommissioned long ago. The 4014 was retired in late 1961, and spent the next 52 years eliciting gasps and whoops of delight at the RailGiants Train Museum in Pomona, California.

The museum had rail enthusiasts from around the world making trips to L.A just to see the Big Boy, says Paul Guercio, the Vice Chairman of the Southern California Chapter of the Railway and Locomotive Historical Society, and a volunteer at RailGiants since 1989.

“Virtually everyone responded to it with awe just because of the sheer size of it,” Guercio says. “Most serious railfans had seen a Big Boy at one time or another, as there are eight of them preserved around the country. But even if someone has seen one before, it’s so big that it’s hard to get enough of it.”

How Big Is Big?

We’ll get into Union Pacific’s Olympian restoration of the 4014, but first we need to get some numbers out of the way. Big Boys they were and are: At 132 feet long, their frames had to be articulated, essentially, hinged so they could navigate curves. They weigh 1.2 million pounds, which means that any long-term forward motion necessitated their 56,000-pound coal capacity and their 24,000-gallon water capacity to perpetually push those massive pistons with steam.

The girth required a 4-8-8-4 wheel configuration to keep that thing rock-steady on the rails. With a puny 7,000 horsepower, Big Boys had a maximum tractive power of 135,375 pounds. Don’t worry if you can’t easily envision 135,375 pounds. Just know it could pull like hell.

Though the 4014 wasn’t operational when it arrived at Rail Giants, in later exhibition years its general maintenance was sustained by generous grants from entities like ExxonMobil and Boeing. There were some challenges. “One factor was the availability of tools,” says Guercio. “Basically, the organization had no tools, so members supplied their own.”

Of course, most people don’t own tools of the size and type needed to maintain something as large as a Big Boy.

“Once again, I was aided by ExxonMobil, who loaned me tools over weekends to work at the museum,” Guercio says. “My colleagues at work were also very helpful. While there were no steam locomotives in an oil refinery, there were plenty of very large machines and boilers, so I had access to the knowledge base of people who do this type of maintenance work every day. It was a privilege to work on such a magnificent machine.”

Diesel Pulled a Fast One

Even mild rail enthusiasts know that steam engines were being supplanted by diesel-electrics as early as the 1940s. Blame economics: Instead of a massive single steam engine, diesels could be daisy-chained together and controlled from the lead engine. Steam engines can take hours to build up steam to power the locomotive and required near-continuous servicing, much unlike the “get in and go” diesel.

But Union Pacific never abandoned steam completely. The railroad’s 844 steam operated in revenue capacities until the early ‘60s and has since been employed essentially for excursion trains aimed at railroad aficionados. The 844 is no slouch itself in regards to size, but it’s still a little brother to Big Boy.

The last 40 years have seen a growing movement to acquire and restore industrial-sized steam locomotives—mostly by private groups of enthusiasts. The one question, oft repeated, was “When will someone restore a Big Boy?” The conventional wisdom was, “Never. Too big and complex a project.”

Several Big Boys had been preserved in varying states of condition around the country, gifts to museums and municipalities from Union Pacific. But as a practical matter, nobody had the industrial capacity to even consider restoring one—except for Union Pacific.

When Union Pacific decided to bring a Big Boy back to life, they toured the country to examine the eight existing engines to see which was most suitable. To their surprise, Rail Giants and Big Boy alumni had been lubricating the 4014’s running gear for decades in hopes it might one day run again.

“I don’t think anyone really thought it would ever happen, but there was a very few of us who had hope and did our best to preserve it so that if the day ever came, 4014 would be a good candidate,” says Guercio. “My reaction to UP’s request was to give them the keys to the locomotive on the spot. There was no doubt they could take better care of it than the museum ever could, and if anyone was going to restore one to operational status, there was no one better than Union Pacific.”

Run Like the Dickens

Restoring something as complex as the boiler and running gear of a supersized vintage locomotive isn’t for the faint of heart. But Union Pacific’s designers, machinists, and engineers had both technical expertise with steam and the serious railfan’s enthusiasm to pursue the work through all the tangled courses it would take.

Ed Dickens, Senior Manager of Steam and Heritage operations at UP, headed a team of nine full-time employees, who worked tirelessly on the locomotive for two and a half years.

Heavily weighted in the decision to restore the 4014 was its boiler. In a mid-restoration video in early 2018, Dickens says, “I wanted the 4014 over all the other Big Boys for this reason: It had less corrosion and it was less worn out. Some of the machines on other locomotives were a little bit better, but on balance the boiler was in the best condition. When you’re talking about a big 300-pound-pressure vessel, you want to have 100 percent of that boiler in the best condition you can make it.”

The Big Boys were significant design and engineering achievements; it’s not hyperbole to say they were an ultimate expression of American art and science. Their service record of pulling huge loads of freight trains across steep grades in Utah’s Wasatch Mountains and the Rockies is stellar. And records, painstakingly kept at UP, were integral to the successful restoration of the engine. Union Pacific not only had detailed operating records and maintenance histories, but they also had the original blueprints, schematics, and design documents of the locomotives.

Bend Some Steel, Boot Some CPUs

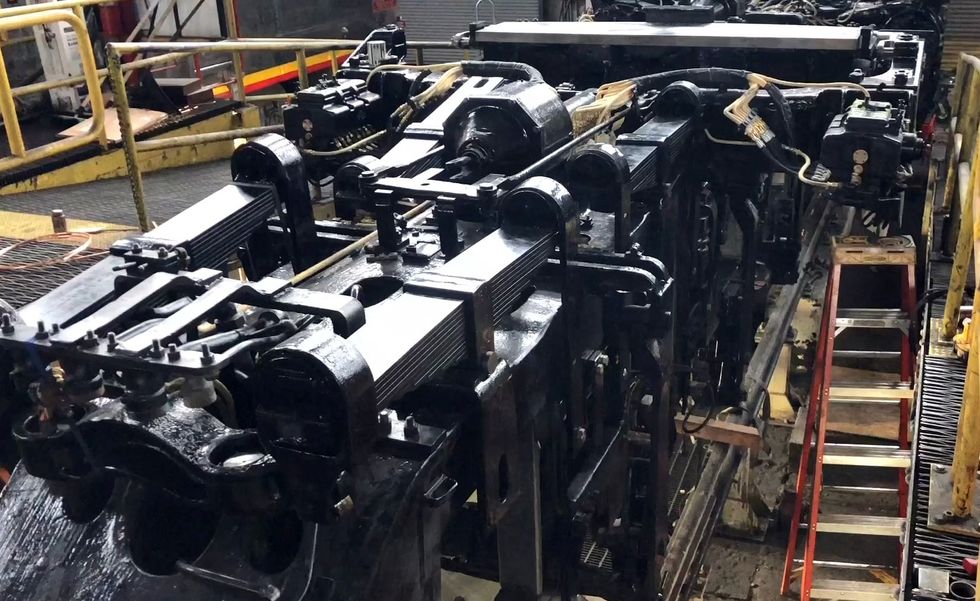

The original—and gigantic—steam shop in Cheyenne, Wyoming had been converted to service diesel locomotives; the 4014’s restoration demanded the reconfiguring of that steam shop. Further digging into rail archeology: some original steam-engine tools had to be reconditioned or remanufactured.

That these were not small undertakings can’t be overstated. Dickens and his team farmed out the fabrication of the biggest needed parts to highly selected vendors, while hundreds of other parts were fabricated in Cheyenne based on UP’s original Big Boy designs.

“I don’t know if anybody’s ever had an engine and tender come apart on you at 60 miles an hour, but it’s not something I want to live through, so we’re gonna go with new parts,” Dickens says in the video. “We’re talking about a Big Boy: We weren’t just going to restore it enough to get it running. We wanted to do everything we could to make sure the railroad has the best serviceable locomotive we can, which means it’s not going to be cheap, it’s not going to be easy, and we’re not going to be done tomorrow.”

Dickens says he and his team would’ve done a disservice to railfans if they didn’t properly handle the steam locomotives. “You want to see them fired correctly,” he says in the video, “not a bunch of smoke and a bunch of amateur stuff going on that eventually can damage the locomotive and make your life really hard.”

Part of making those good parts involved something much more modern than forges and lathes: Dickens and crew used modern computer-aided design software (CAD) to achieve spec accuracy for parts as good or better than the original. He had his choice of steels and other materials superior to bygone production, as well as the luxury of making modern improvements to piping and other systems.

So Dickens took the original drawings and his team’s foreman, Austin Baker, redrew them in their CAD system. He estimates about 60 percent of the locomotive is made from newly machined parts.

Thus, Dickens’ goal: “We’ve got to make this thing rock-solid 100 percent, which means it’s subjected to the hydrostatic pressure beyond the maximum allowable working pressure,” he says in the video. “If it fails at 300 psi, we won’t be with you, and others could be hurt. You’ve got a fire in there that’s burning 7,000 horsepower worth of fuel and that heat is conducting through all of those metal surfaces. It’s not like a little pot boiling on your stove.”

Feeding the Beast

Speaking of fuel, Big Boy’s burn no longer comes from thousands of pounds of coal. Coal served the Big Boy’s ravenous appetite in the past, but that tremendous hunger mandated coal and water stops for constant replenishment; at full steam, a Big Boy engine would consume the tender’s coal and water supply in two hours. Converting the system to burn fuel oil solved that problem, and was a bit more environmentally conscious as well.

Reflecting on the whole of restoration, Dickens didn’t single out any parts, suppliers or design goal as the biggest challenge. Instead, there was the kind of pressure that builds up in a Big Boy boiler: time.

“The time constraint was our biggest challenge,” Dickens tells Popular Mechanics. “We originally planned five years for restoration; however, we rebuilt the 844 during that window and completed Big Boy’s restoration in about two and a half years. Even though we weren’t working on the Big Boy the entire time, we used our time wisely to source materials, equipment, etc. Some of the parts needed took two years to be delivered.”

Those concerted efforts bore fruit. “There’s an enormous sense of pride, not just for me and the Steam crew, but the entire company. Many, many departments—from Corporate Relations to Supply and Operating—played a part in making the restoration a success,” says Dickens.

What’s in a Name?

The locomotives were originally designated “Wasatch Class” engines. But that name went nowhere once a stealthy factory hand got to work.

“One other thought that I feel still holds true today just as it did in 1941,” says Guercio, “is that there’s a lot in the name, an appeal that transcends generations. The simplicity of a chalk mark written on the smokebox door by an unknown machinist. The name stuck, and just as Union Pacific took every opportunity to capitalize on it back in the 1940s, it still works today. There’s just nothing like a Big Boy.”

And the locomotive’s sound lives up to the name.

“The sound of the steam locomotive is something that it gets in your mind, and maybe that was the thing that really got me into steam locomotives: the whistle and the sound they made,” Dickens says in the video. “Being of a different generation that had never seen steam locomotives operating, I couldn’t relate to them like the generation that saw them, but there’s something about the steam locomotive that’s just fascinating,” he says.

Rumors on the rail say that Big Boy might be used for special excursions, and possibly even to pull freight again. That particular fascination will have to wait, but on the factual side, we definitively know railfans will have a source of exultation across the Union Pacific system this summer, because the Big Boy is going on tour, with many dates and stops.

If you feel a rumble and hear that signature sound, get to the station. You won’t want to miss it.

Tom Bentley is still trying to figure out what flavor of writer he is, but so far he’s a short story writer, novelist, essayist, travel writer, journalist, and business copywriter. He edits all that stuff too. His singing has been known to frighten the horses. See his lurid website confessions and blog at www.tombentley.com.