/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/72736517/51539859.0.1544234827.0.jpg)

Editor’s note, October 9, 2023: This story was last updated on July 17, 2014, and some information in it may no longer be accurate. For all of Vox’s latest coverage on Israel and Palestine, see our storystream.

Everyone has heard of the Israel-Palestine conflict. Everyone knows it's bad, that it's been going on for a long time, and that there is a lot of hatred on both sides.

But you may find yourself less clear on the hows and the whys of the conflict. Why, for example, did Israel invade the Palestinian territory of Gaza in July 2014, leading to the deaths of hundreds of Palestinian civilians, many of them children? Why did the militant Palestinian group Hamas fire rockets into civilian neighborhoods in Israel? How did this latest round of violence start in the first place — and why do they hate one another at all?

What follows are the most basic answers to your most basic questions. Giant, neon-lit disclaimer: these issues are complicated and contentious, and this is not an exhaustive or definitive account of Israel-Palestine's history or the conflict today. But it's a place to start.

1) What are Israel and Palestine?

That sounds like a very basic question but, in a sense, it's at the center of the conflict.

(BBC)

Israel is an officially Jewish country located in the Middle East. Palestine is a set of two physically separate, ethnically Arab and mostly Muslim territories alongside Israel: the West Bank, named for the western shore of the Jordan River, and Gaza. Those territories are not independent (more on this later). All together, Israel and the Palestinian territories are about as populous as Illinois and about half its size.

Officially, there is no internationally recognized line between Israel and Palestine; the borders are considered to be disputed, and have been for decades. So is the status of Palestine: some countries consider Palestine to be an independent state, while others (like the US) consider Palestine to be territories under Israeli occupation. Both Israelis and Palestinians have claims to the land going back centuries, but the present-day states are relatively new.

2) Why are Israelis and Palestinians fighting?

Israeli soldiers clash with Palestinian stone throwers at a checkpoint outside Jerusalem (AHMAD GHARABLI/AFP/Getty Images)

This is not, despite what you may have heard, primarily about religion. On the surface at least, it's very simple: the conflict is over who gets what land and how it is controlled. In execution, though, that gets into a lot of really thorny issues, like: Where are the borders? Can Palestinian refugees return to their former homes in present-day Israel? More on these later.

The decades-long process of resolving that conflict has created another, overlapping conflict: managing the very unpleasant Israeli-Palestinian coexistence, in which Israel has put the Palestinians under suffocating military occupation and Palestinian militant groups terrorize Israelis.

Those two dimensions of the conflict are made even worse by the long, bitter, violent history between these two peoples. It's not just that there is lots of resentment and distrust; Israelis and Palestinians have such widely divergent narratives of the last 70-plus years, of what has happened and why, that even reconciling their two realities is extremely difficult. All of this makes it easier for extremists, who oppose any compromise and want to destroy or subjugate the other side entirely, to control the conversation and derail the peace process.

The peace process, by the way, has been going on for decades, but it hasn't looked at all hopeful since the breakthrough 1993 and 1995 Oslo Accords produced a glimmer of hope that has since dissipated. The conflict has settled into a terrible cycle and peace looks less possible all the time.

Something you often hear is that "both sides" are to blame for perpetuating the conflict, and there's plenty of truth to that. There has always been and remains plenty of culpability to go around, plenty of individuals and groups on both sides that squandered peace and perpetuated conflict many times over. Still, perhaps the most essential truth of the Israel-Palestine conflict today is that the conflict predominantly matters for the human suffering it causes. And while Israelis certainly suffer deeply and in great numbers, the vast majority of the conflict's toll is incurred by Palestinian civilians. Just above, as one metric of that, are the Israeli and Palestinian conflict-related deaths every month since late 2000.

3) How did this conflict start in the first place?

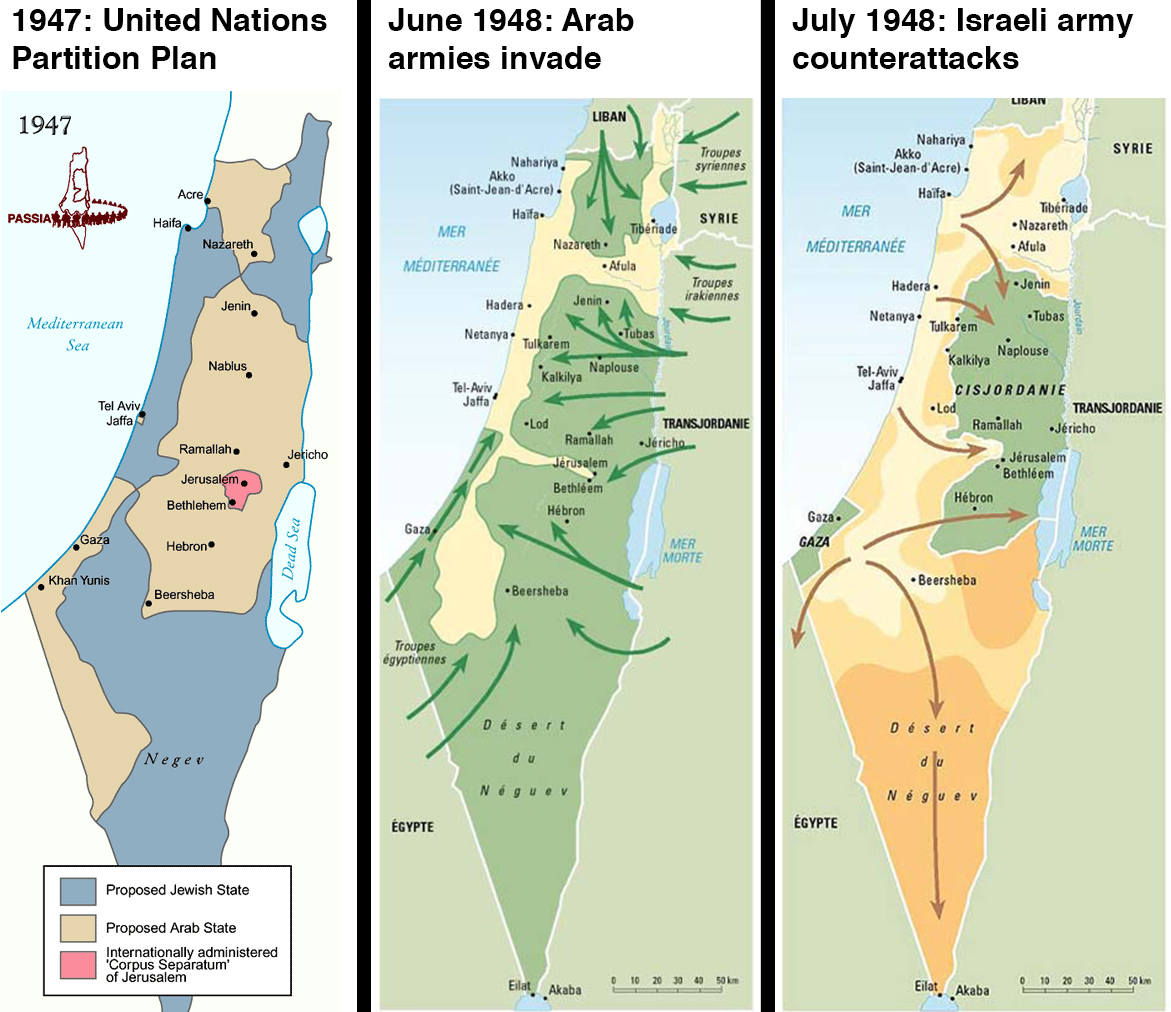

(Left map: Passia; center and right maps: Philippe Rekacewicz / Le Monde Diplomatique)

The conflict has been going on since the early 1900s, when the mostly-Arab, mostly-Muslim region was part of the Ottoman Empire and, starting in 1917, a "mandate" run by the British Empire. Hundreds of thousands of Jews were moving into the area, as part of a movement called Zionism among mostly European Jews to escape persecution and establish their own state in their ancestral homeland. (Later, large numbers of Middle Eastern Jews also moved to Israel, either to escape anti-Semitic violence or because they were forcibly expelled.)

Communal violence between Jews and Arabs in British Palestine began spiraling out of control. In 1947, the United Nations approved a plan to divide British Palestine into two mostly independent countries, one for Jews called Israel and one for Arabs called Palestine. Jerusalem, holy city for Jews and Muslims, was to be a special international zone.

The plan was never implemented. Arab leaders in the region saw it as European colonial theft and, in 1948, invaded to keep Palestine unified. The Israeli forces won the 1948 war, but they pushed well beyond the UN-designated borders to claim land that was to have been part of Palestine, including the western half of Jerusalem. They also uprooted and expelled entire Palestinian communities, creating about 700,000 refugees, whose descendants now number 7 million and are still considered refugees.

The 1948 war ended with Israel roughly controlling the territory that you will see marked on today's maps as "Israel"; everything except for the West Bank and Gaza, which is where most Palestinian fled to (many also ended up in refugee camps in neighboring countries) and are today considered the Palestinian territories. The borders between Israel and Palestine have been disputed and fought over ever since. So has the status of those Palestinian refugees and the status of Jerusalem.

That's the first major dimension of the conflict: reconciling the division that opened in 1948. The second began in 1967, when Israel put those two Palestinian territories under military occupation.

4) Why is Israel occupying the Palestinian territories?

A Palestinian boy next to the Israeli wall around the town of Qalqilya (David Silverman/Getty Images)

This is a hugely important part of the conflict today, especially for Palestinians.

Israel's military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza began in 1967. Up to that point, Gaza had been (more or less) controlled by Egypt and the West Bank by Jordan. But in 1967 there was another war between Israel and its Arab neighbors, during which Israel occupied the two Palestinian territories. (Israel also took control of Syria's Golan Heights, which it annexed in 1981, and Egypt's Sinai Peninsula, which it returned to Egypt in 1982.)

Israeli forces have occupied and controlled the West Bank ever since. It withdrew its occupying troops and settlers from Gaza in 2005, but maintains a full blockade of the territory, which has turned Gaza into what human rights organizations sometimes call an "open-air prison" and has pushed the unemployment rate up to 40 percent.

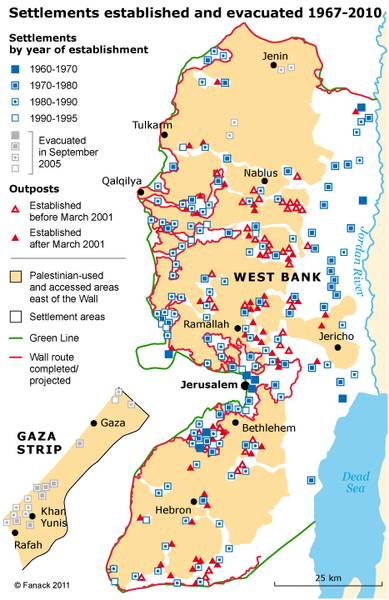

(Fanack)

Israel says the occupation is necessary for security given its tiny size: to protect Israelis from Palestinian attacks and to provide a buffer from foreign invasions. But that does not explain the settlers.

Settlers are Israelis who move into the West Bank. They are widely considered to violate international law, which forbids an occupying force from moving its citizens into occupied territory. Many of the 500,000 settlers are just looking for cheap housing; most live within a few miles of the Israeli border, often in the around surrounding Jerusalem.

Others move deep into the West Bank to claim land for Jews, out of religious fervor and/or a desire to see more or all of the West Bank absorbed into Israel. While Israel officially forbids this and often evicts these settlers, many are still able to take root.

In the short term, settlers of all forms make life for Palestinians even more difficult, by forcing the Israeli government to guard them with walls or soldiers that further constrain Palestinians. In the long term, the settlers create what are sometimes called "facts on the ground": Israeli communities that blur the borders and expand land that Israel could claim for itself in any eventual peace deal.

The Israeli occupation of the West Bank is all-consuming for the Palestinians who live there, constrained by Israeli checkpoints and 20-foot walls, subject to an Israeli military justice system in which on average two children are arrested every day, stuck with an economy stifled by strict Israeli border control, and countless other indignities large and small.

5) Can we take a quick music break?

Music breaks like this are usually an opportunity to step back and appreciate the aspects of a people and culture beyond the conflict that has put them in the news. And it's true that there is much more to Israelis and Palestinians than their conflict. But music has also been a really important medium by which Israelis and Palestinians deal with and think about the conflict. The degree to which the conflict has seeped into Israel-Palestinian music is a sign of how deeply and pervasively it effects Israelis and Palestinians.

Above, from the wealth of Palestinian hip-hop is the group DAM, whose name is both an acronym for Da Arabian MCs and the Arabic verb for "to last forever." The group has been around since the late 1990s and are from the Israeli city of Lod, Israeli citizens who are part of the country's Arab minority. The Arab Israeli experience, typically one of solidarity with Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza and a sense that Arab-Israelis are far from equal in the Jewish state, comes through in their music, which is highly political and deals with themes of disenfranchisement and dispossession in the great tradition of American hip-hop.

Christiane Amanpour interviewed DAM about their music last year. Above is their song "I Don't Have Freedom," full English lyrics of which are here, from their 2007 album Dedication. Sample line: "We've been like this more than 50 years / Living as prisoners behind the bars of paragraphs /Of agreements that change nothing."

Now here is a sample of Israel's wonderful jazz scene, one of the best in the world, from the bassist and band leader Avishai Cohen. Cohen is best known in the US for his celebrated 2006 instrumental album Continuo, but let's instead listen to the song "El Hatzipor" from 2009's Aurora.

The lyrics are from an 1892 poem of the same name, meaning "To the Bird," by the Ukrainian Jewish poet Hayim Nahman Bialik. The poem (translated here) expresses the hopeful yearning among early European Zionists like Bialik to escape persecution in Europe and find salvation in the holy land; that it still resonates among Israelis over 100 years later is a reminder of both the tremendous hopes invested in the dream of a Jewish state, and perhaps the sense that this dream is still not secure.

6) Why is there fighting today between Israel and Gaza?

On the surface, this is just the latest round of fighting in 27 years of war between Israel and Hamas, a Palestinian militant group that formed in 1987 seeks Israel's destruction and is internationally recognized as a terrorist organization for its attacks targeting civilians — and which since 2006 has ruled Gaza. Israeli forces periodically attack Hamas and other militant groups in Gaza, typically with air strikes but in 2006 and 2009 with ground invasions.

The latest round of fighting was sparked when members of Hamas in the West Bank murdered three Israeli youths who were studying there on June 10. Though the Hamas members appear to have acted without approval from their leadership, which nonetheless praised the attack, Israel responded by arresting large numbers of Hamas personnel in the West Bank and with air strikes against the group in Gaza.

After some Israeli extremists murdered a Palestinian youth in Jerusalem and Israeli security forces cracked down on protests, compounding Palestinian outrage, Hamas and other Gaza groups launched dozens of rockets into Israel, which responded with many more air strikes. So far the fighting has killed one Israeli and 230 Palestinians; two UN agencies have separately estimated that 70-plus percent of the fatalities are civilians. On Thursday, July 17, Israeli ground forces invaded Gaza, which Israel says is to shut down tunnels that Hamas could use to cross into Israel.

That get backs to that essential truth about the conflict today: Palestinian civilians endure the brunt of it. While Israel targets militants and Hamas targets civilians, Israel's disproportionate military strength and its willingness to target militants based in dense urban communities means that Palestinians civilians are far more likely to be killed than any other group.

But those are just the surface reasons; there's a lot more going on here as well.

7) Why does this violence keep happening?

Palestinian youth throw stones at an Israeli tank in 2003. (SAIF DAHLAH/AFP/Getty Images)

The simple version is that violence has become the status quo and that trying for peace is risky, so leaders on both ends seem to believe that managing the violence is preferable, while the Israeli and Palestinian publics show less and less interest in pressuring their leaders to take risks for peace.

Hamas's commitment to terrorism and to Israel's destruction lock Gazans into a conflict with Israel that can never be won and that produces little more than Palestinian civilian deaths. Israel's blockade on Gaza, which strangles economic life there and punishes civilians, helps produce a climate that is hospitable to extremism, and allows Hamas to nurture a belief that even if Hamas may never win, at least refusing to put down their weapons is a form of liberation.

Many Palestinians in Gaza naturally compare Hamas to Palestinian leaders in the West Bank, who have emphasized peace and compromise and negotiations — only to have been rewarded with an Israeli military occupation that shows no sign of ending and ever-expanding settlements. This is not to endorse that logic, but it is not difficult to see why some Palestinians might conclude that violent "resistance" is preferable.

That sense of Palestinian hopelessness and distrust in Israel and the peace process has been a major contributor to violence in recent years. In the early 2000s, there was also a lot of fighting between Israel and Palestinians in the West Bank. This was called the Second Intifada (uprising), and followed a less-violent Palestinian uprising against the occupation in the late 1980s. In the Second Intifada, which was the culmination of Palestinian frustration with the failure of the 1990s peace process, Palestinian militants adopted suicide bombings of Israeli buses and other forms of terror. Israel responded with a severe military crack-down. The fighting killed approximately 3,200 Palestinians and 1,100 Israelis.

A 2002 Palestinian bus bombing that killed 18 in Jerusalem (Getty Images)

It's not just Palestinians, though: many Israelis also increasingly distrust Palestinians and their leaders and see them as innately hostile to peace. In the parlance of Israel-Palestine, the expression for this attitude is, "We don't have a partner for peace." That feeling became especially deep after the Second Intifada; months of bus bombings and cafe bombings made many Israelis less supportive of peace efforts and more willing to accept or simply ignore the occupation's effects on Palestinians.

This sense of apathy has been further enabled by Israel's increasingly successful security programs, such as the Iron Dome system that shoots down Gazan rockets, which insulates many Israelis from the conflict and makes it easier to ignore. Public support for a peace deal that would grant Palestine independence, once high among Israelis, has dropped. Meanwhile, a fringe movement of right-wing Israeli extremists has become increasingly violent, particularly in the West Bank where many live as settlers, further pulling Israeli politics away from peace and thus allowing the conflict to drift.

8) How is the conflict going to end?

The Dome of the Rock (at left with gold dome) is one of the holiest sites in Islam and sits atop the ancient Temple Mount ruins, the Western Wall of which (at right) is the holiest site in Jerusalem. You can see how this would create logistical problems. (Uriel Sinai/Getty Images)

There are three ways the conflict could end. Only one of them is both viable and peaceful — the two-state solution — but it is also extremely difficult, and the more time goes on the harder it gets.

One-state solution: The first is to erase the borders and put Israelis and Palestinians together into one equal, pluralistic state, called the "one-state solution." Very few people think this could be viable for the simple reason of demographics; Arabs would very soon outnumber Jews. After generations of feeling disenfranchised and persecuted by Israel, the Arab majority would almost certainly vote to dismantle everything that makes Israel a Jewish state. Israelis, after everything they've done to finally achieve a Jewish state after thousands of years of their own persecution, would never surrender that state and willingly become a minority among a population they see as hostile.

Destruction of one side: The second way this could end is with one side outright vanquishing the other, in what would certainly be a catastrophic abuse of human rights. This is the option preferred by extremists such as Hamas and far-right Israeli settlers. In the Palestinian extremist version, Israel is abolished and replaced with a single Palestinian state; Jews become a minority, most likely replacing today's conflict with an inverse conflict. In the Israeli extremist version, Israel annexes the West Bank and Gaza entirely, either turning Palestinians into second-class citizens in the manner of apartheid South Africa or expelling them en masse.

Two-state solution: The third option is for both Israelis and Palestinians to have their own independent states; that's called the "two-state solution" and it's advocated by most everyone as the only option that would create long-term peace. But it requires working out lots of details so thorny and difficult that it's not clear if it will, or can, happen. Eventually, the conflict will have dragged on for so long that this solution will become impossible.

9) Why is it so hard to make peace?

Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres, and Israeli Premier Yitzhak Rabin hold Nobel Peace Prizes won in 1994 for their 1993 Oslo Accords. A follow-on agreement in 1995 was the last major Israeli-Palestinian peace deal. (Photo by Yaakov Saar/GPO via Getty Images)

The one-state solution is hard because there is no viable, realistic version that both sides would accept. In theory, the two-state solution is great. But it poses some very difficult questions. Here are the four big ones and why they're so tough to solve. To be clear, these aren't abstract concepts but real, heavily debated issues that have sunk peace talks before:

Jerusalem: Both sides claim Jerusalem as their capital; it's also a center of Jewish and Muslim (and Christian) holy sites that are literally located physically on top of one another, in the antiquity-era walled Old City that is not at all well shaped to be divided into two countries. Making the division even tougher, Israeli communities have been building up more and more in and around the city.

West Bank borders: There's no clear agreement on where precisely to draw the borders, which roughly follow the armistice line of the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, especially since hundreds of thousands of Israeli settlers have built up suburban-style communities just on the Palestinian side of the line. This one is not actually impossible — Israel could give Palestine some land as part of "land swaps" in exchange for settler-occupied territory — but it's still hard. The more time goes on, the more settlements expand, the harder it becomes to create a viable Palestinian state.

Refugees: This one is really hard. There are, officially, seven million Palestinian refugees, who are designated as such because their descendants fled or were expelled from what is today Israel; places like Ramla and Jaffa. Palestinians frequently ask for what they call the "right of return": permission to return to their land and live with full rights. That sounds like a no-brainer, but Israel's objection is that if they absorb seven million Palestinian returnees, then Jews will become a minority, which for the reasons explained above Israelis will never accept. There are ideas to work around the problem, like financial restitution, but no agreement on them.

Security: This is another big one. For Palestinians, security needs are simple: a sovereign Palestinian state. For Israelis, it's a bit more complicated: Israelis fear that an independent Palestine could turn hostile and ally with other Middle East states to launch the sort of invasion Israel barely survived in 1973. Maybe more plausibly, Israelis worry that Hamas would take over an independent West Bank and use it to launch attacks on Israelis, as they've done with Gaza. Any compromise would likely involve Palestinians giving up some sovereignty, for example promising permanent de-militarization or allowing an international peacekeeping force, and after years of feeling heavily abused by strong-handed Israeli forces, Palestinians are not eager about the idea of Israel having veto power over their sovereignty and security.

Those are all very difficult problems. But here's the thing: time is running out. The more that the conflict drags on, the more difficult it will be to solve any of these issues, much less all of them. That will make it harder and harder for Israel to justify keeping Gaza under blockade and the West Bank under occupation; eventually it will have to unilaterally withdraw, which the current leadership opposes, or it will have to annex the territories and become either an apartheid-style state that denies full rights to those new Palestinian citizens or abandon its Jewish state.

Meanwhile, extremism and apathy and distrust are rising on both sides. The violence of the conflict is becoming status quo, a regularly recurring event that is replacing the peace process itself as the way by which the conflict advances. It is making things worse for Israelis and Palestinians alike all the time, and unless they can break from the hatred and violence long enough to make peace, that will continue.