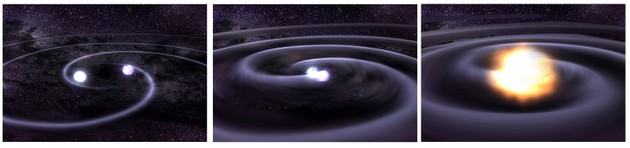

After decades of anticipation, we have directly detected gravitational waves—ripples in spacetime traveling at the speed of light through the universe. Scientists at LIGO (the Laser Interferometic Gravitational-wave Observatory) have announced that they have measured waves coming from the inspiral of two massive black holes, providing a spectacular confirmation of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity, whose hundredth anniversary was celebrated just last year.

Finding gravitational waves indicates that Einstein was (once again) right, and opens a new window onto energetic events occurring around the universe. But there’s a deeper lesson, as well: a reminder of the central importance of locality, an idea that underlies much of modern physics.

Locality can be thought of as the simple notion that “what happens here is affected by what’s happening nearby, not by what’s happening far away.” Signals and influences don’t zip instantaneously across the universe; they take time to propagate through space. Sounds obvious, but before Einstein came along, that’s not how we thought gravity worked.

Between the years 1687 and 1915, our best understanding of gravity was the one proposed by Sir Isaac Newton. It was Newton who formulated the famous Inverse Square Law, which says that the strength of the gravitational force between two objects is proportional to the mass of each of them, and also to the inverse of the square of the distance between them. Roughly: Gravity is stronger when objects are heavier, and when they’re closer to each other.

The force of gravity has both a strength and a direction. In our everyday lives, we feel a force pointing basically toward the center of the Earth. According to Newton, Earth’s gravity stretches far away, literally throughout the universe, though it grows weaker the further away you get. As the Earth moves, its gravitational field shifts along with it, instantly, everywhere in the universe; that instantaneous change is what gives Newtonian gravity its nonlocal character. Other stars and planets also contribute to the total gravitational force at any particular location in space, but in principle we could imagine isolating the Earth’s contribution.

We can even imagine sending signals this way. Everything causes gravity, so just waving a bowling ball back and forth causes changes in the gravitational force instantly throughout the cosmos. In practice it would be hard to pick out the force from one tiny object, but by thought-experiment standards it’s not that different from what real radios do with electromagnetic waves. A gravity detector far away could measure how we were waving our bowling ball, and we could use Morse code (or whatever) to send messages to it.

In a Newtonian world, those messages would travel instantly over infinitely far distances. Not only do they travel faster than light, they travel faster than anything.

Newton himself never liked this feature of his own theory. It wasn’t primarily the instantaneous speed of gravity, but the fact that the force seemed to propagate through empty space, rather than through a medium like the air. He found this “action at a distance” distasteful, but he left its ultimate solution “to the Consideration of my readers.”

These days we’re less hung up on the need for a “medium” through which forces propagate. Spacetime itself is good enough for modern physics. We say that spacetime is suffused with different kinds of fields—including electromagnetic fields and the gravitational field—and disturbances in them can propagate even through empty space. That’s what electromagnetic waves are (light, X-rays, microwaves, radio waves), as well as the newly-discovered gravitational waves.

To modern physicists, it’s the “instantaneous” part of Newton’s theory that causes discomfort, not the lack of a medium for gravity to travel through. Would you want to live in a world where technologically advanced aliens in the Andromeda galaxy could—in principle—eavesdrop on what you were saying right now?

Happily, Einstein’s theory of relativity tells a different story.

Einstein’s general relativity is a theory of gravity. It says that spacetime can be curved, and we feel the effects of that curvature as the gravitational force. According to relativity, the speed of light puts an absolute limit on how fast influences can travel through space. The Andromeda galaxy is two and a half million light years away, so it would take at the very least five million years to send a signal there and get a response back.

We’ve all heard about this speed-of-light barrier, which applies to gravitational waves just as much as everything else in the universe. But let’s think a bit more deeply about why there is such a limit at all. That’s where locality comes in.

Drop a pebble into a still pond. Small waves ripple outward in a circular pattern. We naturally think of those waves as “things” that “travel” through the water, but at the same time we recognize that there is a deeper description. The water is made of molecules, and those molecules keep moving around and pushing on other molecules. At this microscopic level of description, molecules in the pebble pushed on water molecules at the location where the pebble entered the water. Those molecules in turn pushed on other water molecules nearby, and those pushed on ones a bit farther out, and so on. It’s the collective action of all those molecules together that gives us the impression of “waves traveling through water.”

The molecules themselves only interact when they are very close by—when they literally bump into each other. The pebble doesn’t instantly affect all the water in the pond. It affects water molecules in one location, which then affect those nearby, in a chain that ripples to the edges of the pond. That’s locality in action: Even though the waves might travel impressive distances, at a deeper level it’s just each molecule talking to others right next door. There is no action at a distance, spooky or otherwise.

According to Einstein, every action in the universe is like that. If we move the Earth (or a massive black hole), its gravitational field doesn’t instantly change all throughout the universe. The field changes right where the Earth is, and that change affects the field nearby, and that change affects the field just a little further out, and so on down the line. That’s the origin of gravitational waves: disturbances in the gravitational field, rippling through spacetime at the speed of light, just like the ripples we get from throwing a pebble into a pond.

As far as we know, of course, spacetime isn’t made of molecules, or even anything analogous. Spacetime simply is—it’s one of the fundamental ingredients in our best current theories of the universe. We can’t really explain why locality is such an important part of the physical world; we just accept it as a brute fact.

That may not be the final answer. As good as Einstein’s theory of general relativity is, it suffers from the fatal flaw of not being compatible with quantum mechanics, our best theory of the universe on very small scales. Most physicists feel that quantum mechanics will ultimately prove to be more fundamental than relativity, which is to say that the two theories will be reconciled by finding some quantum theory that reproduces general relativity in the right circumstances.

In quantum mechanics, locality doesn’t seem like nearly as important a feature as it is in relativity. Indeed, in some ways quantum mechanics is flagrantly nonlocal—that’s the feature of “entanglement,” a subject for another day. Right now, let’s simply let ourselves imagine a future in which we do understand the underlying quantum theory of the universe, in which general relativity appears simply as a useful approximation. Someday, the very notions of space, time, and locality may turn out to be emergent, just as water waves emerge from the molecules below.

To get there, we need to learn everything we can about how spacetime works in the real world, not just in the minds of theoretical physicists. Discovering gravitational waves is a major milestone along that path.