In August, an organization called the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee announced that prisoners in at least 17 states had pledged to stage a strike to protest prison conditions. It is unclear how many inmates actually took part in the 19-day strike, but organizers said “thousands“ refused to work, staged sit-ins, and turned away meals to demand “an immediate end to prison slavery.” Nationwide, inmates’ labor is essential to running prisons. They cook, clean, do laundry, cut hair, and fulfill numerous administrative tasks for cents on the dollar, if anything, in hourly pay. Prisoners have been used to package Starbucks coffee and make lingerie. In California, inmates volunteer to fight the state’s wildfires for just $1 an hour plus $2 per day.

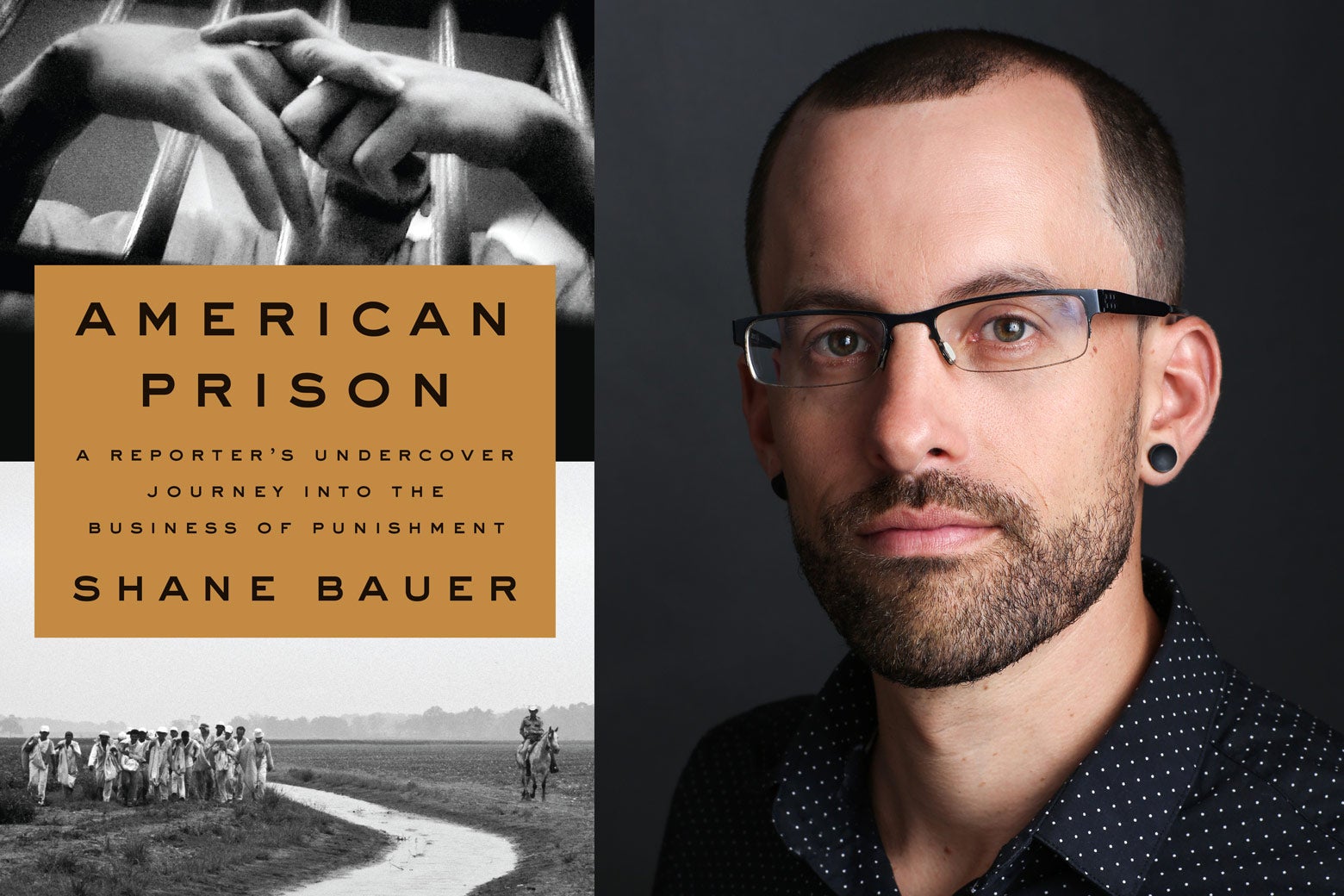

The link between prison labor and slavery is not merely rhetorical. At the end of the Civil War, the 13th amendment abolished slavery “except as a punishment for a crime.” This opened the door for more than a century of forced labor that was in many ways identical to, and in some ways worse than, slavery. The following is an excerpt from my new book, American Prison: A Reporter’s Undercover Journey Into the Business of Punishment. The book details my time working undercover as a prison guard in a for-profit prison in Louisiana. It also traces the ways in which our prison system evolved out of the attempt of Southern businessmen to keep slavery alive.

A few years after the Civil War ended, Samuel Lawrence James bought a plantation on a sleepy bend of the Mississippi River in Louisiana’s West Feliciana Parish. It was known as Angola, named for the country of origin of many of the people who were once enslaved there. Before the war, it produced 3,100 bales of cotton a year, an amount few Southern plantations could rival. For most planters, those days seemed to be over. Without slaves, it was impossible to reach those levels of production.

But James was optimistic. Slavery may have been gone, but something like it was already beginning to come back in other states. While antebellum convicts were mostly white, 7 out of 10 prisoners were now black. In Mississippi, “Cotton King” Edmund Richardson convinced the state to lease him its convicts. He wanted to rebuild the cotton empire he’d lost during the war, and, with its penitentiary burned to ashes, the state needed somewhere to send its prisoners. The state agreed to pay him $18,000 per year for their maintenance, and he could keep the profits derived from their labor. With the help of convict labor, he would become the most powerful cotton planter in the world, producing more than 12,000 bales on 50 plantations per year. Georgia, whose penitentiary had been destroyed by Gen. Sherman, was leasing its convicts to a railroad builder. Alabama had leased its convicts to a dummy firm that sublet them for forced labor in mines and railroad-construction camps throughout the state.

There was no reason Louisiana couldn’t take the same path. Black Americans were flooding the penitentiary system, mostly on larceny convictions. In 1868, the state had appropriated three times as much money to run the penitentiary as it had the previous year. It was the perfect time to make a deal, but someone beat James to it. A company called Huger and Jones won a lease for all of the state prisoners. Barely had the ink dried on the contract before James bought them out for a staggering $100,000 (about $1.7 million in 2018 dollars). James worked out a 21‑year lease with the state, in which he would pay $5,000 the first year, $6,000 the second, and so on up to $25,000 for the 21st year in exchange for the use of all Louisiana convicts. All profits earned would be his. He immediately purchased hundreds of thousands of dollars of machinery to turn the state penitentiary into a three‑story factory. One newspaper called it “the heaviest lot of machinery ever brought in the state.” The prison became capable of producing 10,000 yards of cotton cloth, 350 molasses barrels, and 50,000 bricks per day. It would also produce 6,000 pairs of shoes per week with the “most complete shoe machinery ever set up south of Ohio.” The factory was so large that the Daily Advocate argued it would stimulate Louisiana’s economy by increasing demand for cotton, wool, lumber, and other raw materials.

In 1873, a joint committee of senators and representatives inspected the Louisiana State Penitentiary and found it nearly deserted: “The looms that used to be worked all day and all night, are now silent as the tomb.” The warden and the lessees were not at the prison. “It is pretty difficult to find out who are the lessees or, indeed, whether or not there are any,” the inspectors wrote in their report. Where were the convicts? Almost as soon as James’ prison factory was running, he’d abandoned it. He’d discovered that he could make a lot more money subcontracting his prisoners to labor camps, where they were made to work on levees and railroads. A convict doing levee and railroad work cost one‑twentieth the labor of a wage worker.

Some in Louisiana’s Reconstruction legislature tried to rein in James. In 1875, it forbade convict labor from being used outside prison walls—senators and representatives were concerned it would deprive their constituents of jobs—but James disregarded the ban and kept his labor camps going. A Baton Rouge district attorney sued James for nonpayment of his lease. James ignored him and made no payment for the next six years. He had become untouchable.

Samuel L. James recorded more about how he himself lived than about the people forced to labor for him. James kept a second home in New Orleans where he and his wife would receive the city’s elite. Their “very elegant toilets and cordial hospitality” would be noted in the paper’s gossip columns. After visits to New Orleans, the James family would ride his steamboat back to Angola, eating delicious meals and playing poker on deck, while transporting convicts in the cargo below. On the plantation, the family kept about 50 prisoners in an ill‑ventilated 15‑by‑20‑foot shack located a half-mile from their nine‑bedroom mansion. During the day, some convicts would tend to the expansive yard, its oak, pecan, and fig trees, and the family’s stable out back.

In the mornings, the convict houseboys would bring James coffee in bed and saddle up his horse, which he’d ride out into the fields at daybreak to see that the work had begun. The few scant accounts reporters recorded from prisoners described a dawn‑to‑dusk work regimen, whippings, and being forced to sleep in muddy clothing. While the fieldworkers ate “starvation rations,” James would return to the big house in the morning to a spread of bacon, eggs, grits, biscuits, batter cakes, syrup, coffee, cream, and fruit. At lunchtime, a “little Negro boy” would sit on the stairs and pull a rope that would spin a fan to keep the family cool. The fieldwork continued through the day, but during the hottest hours, the James family slept, rising later to take a ride around the plantation in their carriage.

One day, in 1894, James was doing his rounds when he was struck by a sudden brain hemorrhage. He died soon after, and his body was laid out in the big house for a viewing. When the estate was passed on to his son, it was valued at $2.3 million, the equivalent of about $63 million in 2018.

A convict under James’ lease had a higher chance of death than he would have had as a slave. In 1884, the editor of the Daily Picayune wrote that it would be “more humane to punish with death all prisoners sentenced to a longer period than six years” because the average convict lived no longer than that. At the time, the death rate at six prisons in the Midwest, where convict leasing was nonexistent, was about 1 percent. By contrast, in the deadliest year of Louisiana’s lease, nearly 20 percent of convicts perished. Between 1870 and 1901, about 3,000 Louisiana convicts, most of whom were black, died under James’ regime. Before the war, only a handful of planters owned more than 1,000 slaves, and there is no record of anyone allowing 3,000 valuable human chattel to die. The pattern was consistent throughout the South, where annual convict death rates ranged from about 16 percent to 25 percent, a mortality rate that would rival the Soviet gulags to come. (Gulag death rates during 1942 and 1943 were about 25 percent, according to the Soviet Union’s Interior Ministry records.)

Some American camps were far deadlier than Stalin’s: In South Carolina, the death rate of convicts leased to the Greenwood and Augusta Railroad averaged 45 percent a year from 1877–79. In 1870, Alabama prison officials reported that more than 40 percent of their convicts had died in their mining camps. A doctor warned that Alabama’s entire convict population could be wiped out within three years. But such warnings meant little to the men getting rich off prisoners. There was simply no incentive for lessees to avoid working people to death. In 1883, 11 years before Samuel L. James’ death, one Southern man told the National Conference of Charities and Correction, “Before the war, we owned the negroes. If a man had a good negro, he could afford to take care of him: if he was sick get a doctor. He might even put gold plugs in his teeth. But these convicts: we don’t own ’em. One dies, get another.”

From American Prison: A Reporter’s Undercover Journey Into the Business of Punishment by Shane Bauer. Published by arrangement with Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright 2018 by Shane Bauer.

Slate is an Amazon affiliate and may receive a commission from purchases you make through our links.