The ’60s Soviet Satellite That Crashed Into Wisconsin

When Sputnik IV hit the streets of sleepy Manitowoc, it ushered in the age of space junk.

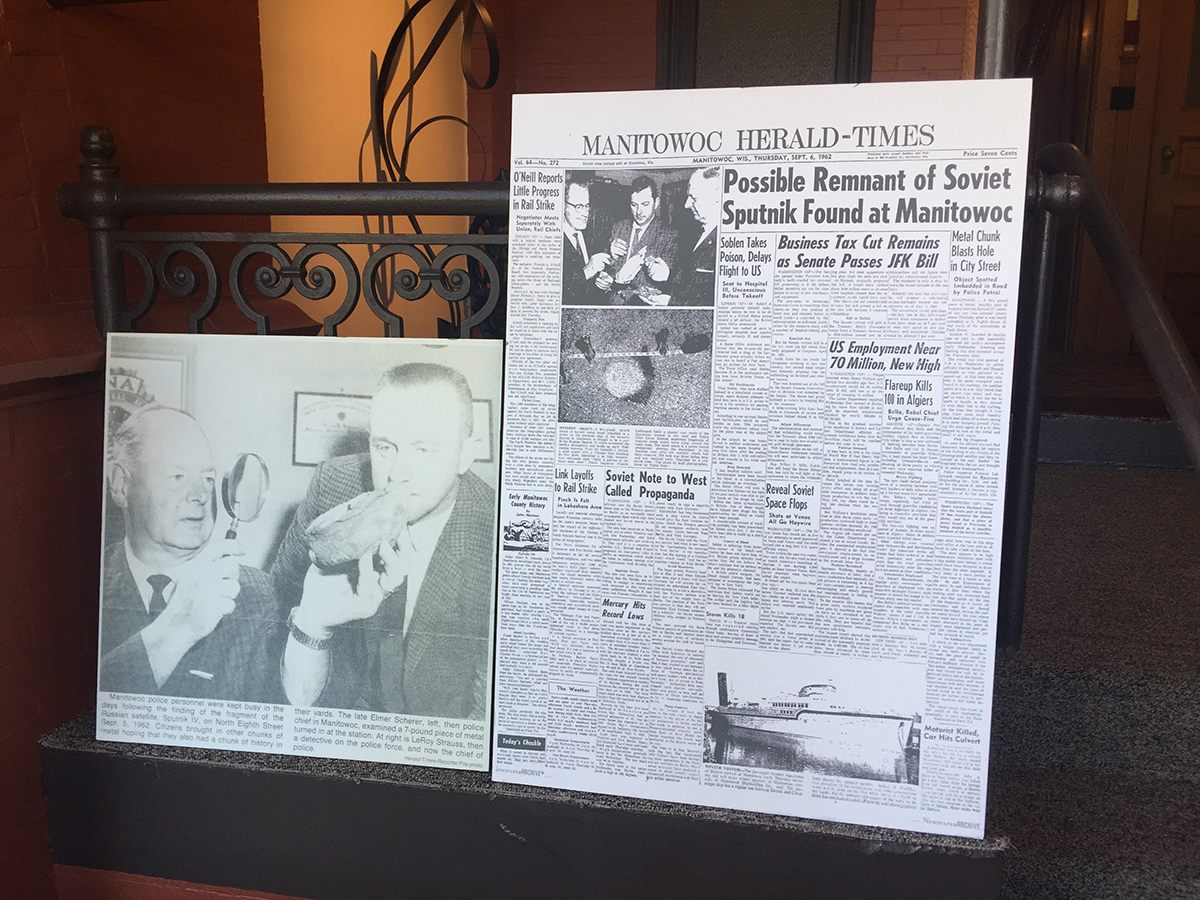

In September 1962, something fell from aloft in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, cracking the asphalt on North 8th Street in front of what’s now the Rahr-West Art Museum.

Dennis Gintner, a Manitowoc-area resident, was a pre-teen at the time. He remembers the to-do about it.

“There was a cop that came along and kicked it off the street,” he says. “Thought it came from a garbage wagon.”

But as the pieces of the mysterious hunk of metal came to light, the town of Manitowoc realized they were dealing with something that was not of this world.

Okay, well, it was only kind of from out of this world. What fell in Manitowoc all of those years ago was a piece of Sputnik IV, a Russian satellite* that had spent two years in orbit. The Soviets lost control of it not long after its May 1960 launch, and the craft’s low orbit meant it would eventually be dragged down to Earth.

Sputnik IV was a test run for several human spaceflight technologies, including communications relays and a life support system with a dummy inside, according to NASA. The dummy, sadly, did not survive re-entry and become a Roswell-like urban legend. The craft was initially meant to come down to Earth but, “After four days of flight, the reentry cabin was separated from its service module and retrorockets were fired, but because of an incorrect attitude the spacecraft did not reenter the atmosphere.”

“Sputnik IV was a test Vostok spacecraft, which was intended for human spaceflight from the first,” Alice Gorman, a senior lecturer at Flinders University in South Australia, says. “Hence, unlike other Sputnik satellites, it was meant to return to the surface, ideally with its precious humanoid cargo intact.

“Throughout the early Space Age, the Soviet Union excelled at these return missions. It’s one reason why there is so little USSR material surviving in orbit from this period.”

Much of the craft burnt up on the way down, but as it fragmented, some smaller pieces were able to survive the passage through the atmosphere. What returned to Earth was probably fewer than 100 lbs of material out of a total of seven tons. Some fragments likely made it into Lake Michigan. Manitowoc is the only place where a piece seemed to make actual landfall. Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, says he’s never seen evidence of “anything but the Manitowoc chunk” coming from Sputnik IV.

What Gintner said about the cops and the garbage truck is what happened. Two police officers, Marvin Bauch and Ronald Rusboldt, found the object in the middle of the street and ignored it at first. When they came back later, they noticed it was too hot to touch and kicked it aside. As news reports of the craft’s re-entry came about, the police went back to the fragment. Eventually, that fragment made its way into the hands of the Smithsonian, which later returned it to the Russians (somewhat against the will of the Russians, “who called it a circus trick” according to Wisconsin Public Radio.) A replica of the fragment sits in Rahr-West today.

“A little way over and it could have gone through somebody’s roof,” Gintner said.

On the weekend of September 8 this year, the town held its annual Sputnikfest. There’s a Ms. Space Debris pageant, though the event is fairly gender neutral. There are costume contests for dogs and kids, some polka and rock bands, plenty of beer, a few authentic Star Wars costumes, and other community fair-like events.

Greg Vadney, executive director of Rahr-West, says the event isn’t necessarily heavy on the space history element. It’s actually meant to drive people to the museum.

“We are a very traditional art museum, so not a lot of people are going to walk through the door readily,” Vadney says.

So 10 years ago, they took advantage of the 1962 event to bring people toward the museum, in what he calls “an excuse to have a party.”

Vadney is not from Manitowoc, but his wife is. The general attitude Vadney has learned about people in the area toward the Sputnik incident is mild curiosity and a shrug.

“It’s equal parts a point of pride because it’s a notable event, but also something that people laugh at,” Vadney says.

Indeed, the event is marked today by a small plaque on the sidewalk, a ring in the middle of the street where the piece fell, and a historical marker. At the time, Gintner said “it was more exciting then because there was a space race going on.”

But for those who study space debris, there’s a little bit more to it.

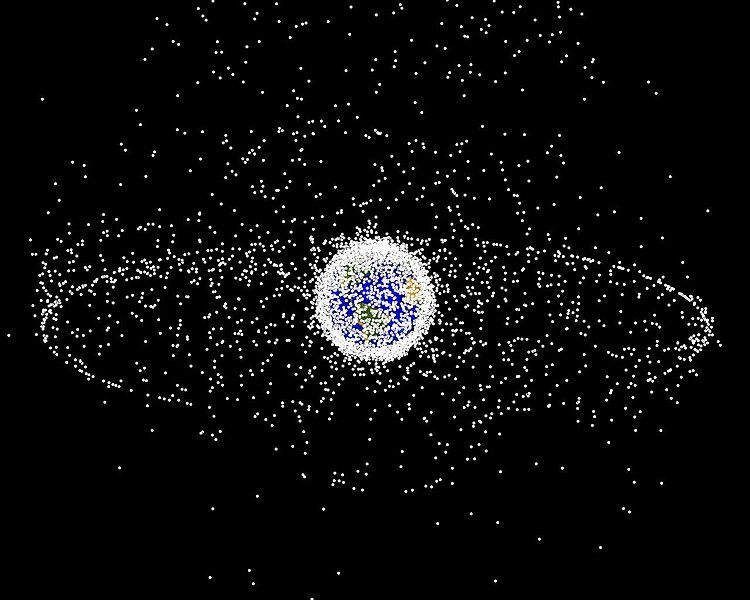

It’s somewhat rare for space junk to make it all the way back from space to Earth relatively intact. The speed of the craft combined with the graduating thickness of our atmosphere spell doom for most—but not all—spacecraft and other objects. Usually, it’s heavier craft like Sputnik IV or fragments of rocket bodies that survive.

Gorman says there are daily re-entries, and that even the bigger satellites that re-enter are broken apart due to the flimsier materials they’re made of. The craft that survive re-entry are usually built out of heavy duty materials.

“Those that do are mostly titanium pressure spheres or stainless steel fuel tanks—both have very high melting temperatures, and they’re often encased in carbon-carbon overwrapping which is also very heat-resistant,” she says.

McDowell says that only one or two pieces actually make it to the ground (or ocean) per year. Gorman places that number at 50 to 200 pieces, though they may be of varying size. And not everything that comes back down is recovered. Intentionally deorbited satellites, brought back to Earth when they’re running out of fuel or almost defunct, are usually aimed at the ocean. “There is just so much sparsely inhabited land mass and huge areas of ocean for space junk to fall into,” Gorman says.

But there are a few outliers beyond Sputnik IV. In 1997, a piece of a rocket booster struck an Oklahoma woman in the shoulder. About one artificial object a day falls to Earth but most don’t make it to the surface, burning up in the atmosphere instead. Of all that material that makes it through that trial by fire, about 6,000 tons of fragmentary material have survived the fall to Earth since the first orbital launch in 1959.

Even Skylab, NASA’s first space station and the space debris fear of the late 1970s, ended up falling over the Australian outback, though a few small pieces scattered over homes there. In 1980, a piece of the Russian satellite Cosmos 749 crashed into a golf course in Eastbourne on the southeast coast of England. (McDowell jokes that it made an “extra hole” in the greenway.) And a 1988 New Scientist feature reports a 635-pound chunk of space junk falling in the midwest in 1970, but is light on details as to what fell.

The only time there’s been a major threat from a returning space object was when Cosmos 954 re-entered over Canada in 1978. It had a radioactive core that broke apart, spreading uranium over the Yukon. Recovery efforts successfully retrieved some, but not all, of the radioactive debris.

Gorman points out that in the mid 1960s the Soviet Union had a fleet of spy satellites called Molniya that were placed in an orbit that would bring them over Russia on any close return to Earth. This ensured that anything with sensitive info wouldn’t fall, say, over Wisconsin.

“There was certainly a concern that a returned bit of space junk could reveal something about the rival space program,” Gorman says. “Soviet spy satellites often used a highly eccentric Molniya orbit, which took the satellite close over the high latitude areas of the USSR with the satellite farthest from the Earth over the US.”

So while Sputnik IV’s crash isn’t unheard of, there may not be a ton of Sputnikfests cropping up, especially considering there were only a couple of landfalls in the United States. And as Gorman says, not many of us will become the Oklahoma woman who was struck by space junk, as “The risk of being hit by falling space junk is really very low.”

Correction: We originally referred to a “Soviet space probe” that is, in fact, a satellite.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook